The following article was published in the January 2013 issue of Podiatry Management, by Dr. Nick Campitelli,DPM, FACFAS

Podiatrist, Foot and Ankle Surgeon. It can also be found on his blog. As he states in an introductory note, “it was written on behalf of the American Academy of Podiatric Sports Medicine and I am honored that Podiatry Management agreed to publish it. It is very exciting to see our profession begin acknowledging that footwear does not have as much to do with injury as we previously thought. Enjoy and spread the word!” — NRC

Treating Running Injuries: Form vs Footwear

Running injuries can be very frustrating for physicians as they can be extremely time-consuming, and stereotypical runners will not curtail their running to resolve an injury. If you tell a runner not to run, most of the time, s(he) will not listen to you and not follow through with your prescribed treatment regimen. This challenge leads many physicians to not treat runners. Added to this frustration is the recommendation of footgear. Whether someone has been running for many years or just starting out, the runner tends to place a lot of emphasis on what shoes to wear. Form is traditionally ignored. Runners, as well as practitioners, will typically make a change of shoes in an attempt to fix an injury.

What most practitioners do not realize is there is no evidence-based literature existing on recommending a running shoe to prevent or reduce injuries.(1-8) Following the popular paradigm of recommending a running shoe based on foot type leads to frustration as there are numerous models being introduced frequently. When we dissect the reasons that we use a particular shoe, the situation becomes even more blurred. There is no clear scientific basis for using one particular shoe model over another for given foot types or pathologies, despite what some manufacturers claim.(1) The term “appropriate shoe” is a misnomer when viewed by the outdated paradigm of selecting a shoe according to arch type, and many are still advocating shoes this way. Even the implementation of orthotics has little if any bearing on reducing or correcting injuries in runners.(9-12)

What most practitioners do not realize is there is no evidence-based literature existing on recommending a running shoe to prevent or reduce injuries.(1-8) Following the popular paradigm of recommending a running shoe based on foot type leads to frustration as there are numerous models being introduced frequently. When we dissect the reasons that we use a particular shoe, the situation becomes even more blurred. There is no clear scientific basis for using one particular shoe model over another for given foot types or pathologies, despite what some manufacturers claim.(1) The term “appropriate shoe” is a misnomer when viewed by the outdated paradigm of selecting a shoe according to arch type, and many are still advocating shoes this way. Even the implementation of orthotics has little if any bearing on reducing or correcting injuries in runners.(9-12)

We also live in a society where people incorrectly believe they have a flat foot or over pronate. Associated with this is the stigma that foot types (especially flat feet) influence injury patterns.(13) This, however, is not true.(14) Evidence suggests that training patterns actually play more of a role in increasing the incidence of running injurious.(15,16) The key is understanding that form and training patterns play more of a role on improving one’s running and at the same time reducing injury.(17)

Common Approach to Running Injuries

Before seeking treatment for an injury, most runners will run through pain thinking that it will eventually resolve. When it finally becomes too severe to continue, medical advice is usually sought. The standard protocol for a physician or sports medicine specialist treating a runner is as follows: 1. Question athletes about how many miles a week they are running 2. Evaluation of footgear 3. The number of miles on the current footgear 4. Biomechanical assessment of feet and lower extremities. If the runner is seen in a more specialized clinic, a gait analysis is sometimes performed. Overpronation is commonly diagnosed, and an effort to control this excessive motion is usually attempted with orthotics. High tech scans and pressure analysis may also be performed, although very little if any applicable information can be generated from this.

Form analysis, on the contrary, focuses more on the runner’s style with respect to foot strike, cadence, and the runner’s overall body posture. It is slowly becoming the panacea to help improve someone’s running and reduce or resolve injuries.(17,18) Runners tend to develop injuries as a result of poor or incorrect form and overuse which many times overlap.(15,19) Debate exists as to what is the “proper form” for running. Proper form will certainly vary from one runner to the next making each runner’s form “ideal” for that individual. There are, however, certain aspects of form a runner should strive to attain – adequate foot strike, cadence, and posture.

Foot Strike

Foot strike is the first aspect that needs to be addressed. There is a common misunderstanding that all aspects of gait, whether walking or running, should begin with a heel strike. Following heel strike, the force is carried laterally, transversing medially upon which it is increased at the 1st MPJ where the propulsion phase ends the final stage of the stance phase before leading into toe off.(20) Much of this thinking is attributed to Root, et al. Over the years, this idea has somehow carried over to running.(20)

The practitioner sometimes will examine the footgear to see if any wear patterns exist that would indicate increased pronation as indicated by wear seen more medially on the heel than laterally. The problem with this pathway is that we have no evidence-based studies to indicate heel striking is the correct way to land when running. In fact, recent studies demonstrate higher injuries among collegiate cross country runners that heel strike as compared to those who forefoot strike.(21,22)

Numerous studies have compared shod and unshod runners and a forefoot strike pattern is adapted among those who run without shoes.(23-27) We all see that elite runners tend to forefoot strike more than slower recreational runners as demonstrated by Larson, et al.(28,29) Evidence exists that the human body has a natural tendency to fore-foot or mid-foot strike when running barefoot or in minimalist shoes.(23,26)

Heel Strike vs Forefoot/Midfoot Strike

By striking the ground with the heel first, the subtalar joint takes the brunt of the force leading to possibly over-utilizing the posterior tibial tendon. We also see that during a rearfoot strike, the forefoot (including the toes) and midfoot joints really serve no purpose in absorbing shock. If, instead, we utilize these joints with a forefoot or midfoot strike, the entire foot can pronate instead of only the subtalar joint which can achieve more absorption of the impact force.(30). By avoiding heel strike, one can utilize the rest of the foot to absorb shock.

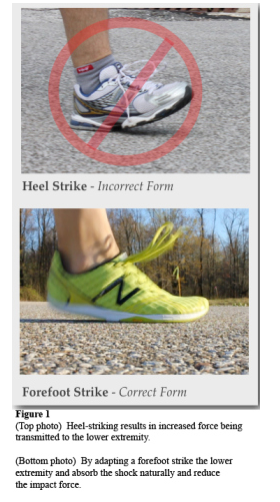

When we forefoot or midfoot strike, we can control the amount of pronation innately by activating our musculature (Figure 1). Consider that one common complaint of those who make the transition to minimalist shoes is “calf pain.” This is due to the activation of the gastroc-soleus, posterior tibial, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus muscles in efforts to slow the heel from striking the ground. They are contracting eccentrically to “slow pronation”. This does not need to be scientifically demonstrated in “future studies” as we already know that if pronation of the foot is dorsiflexion, eversion, and abduction, then thesemuscles collectively are contracting as they are lengthening in order to “slow” pronation. As they become strong enough, they will control the pronation that is occurring during foot strike.(31,32)

Running Shoes

Examining the categories of traditional running shoes reveals that manufacturers have created them according to three foot types – flat foot, normal arch, and high arch. The AAPSM has defined the categories as maximum stability, stability, and neutral. For example, ASICS defines their stability category shoe as “Structured Cushioning.”(33) According to ASCIS, “the structured cushioning is designed for runners who pronate slightly more than normal and generally have a normal arch.”(33) This infers that the runner is heel striking. Otherwise, why would there be a need to control motion? Some of the normal pronation that is encountered when a runner forefoot or midfoot strikes could be inhibited by this motion-controlling apparatus.

Why then are running shoes created with a thick cushioned heel and motion control support? That question is debatable, but it is clear that over the past 40 years we have seen no reduction in injury rates and marathon times have remained unchanged. Many physicians still abide by the rule of changing your shoes every 300-500 miles. This became popular after a study in 1984 that demonstrated shock absorption loss after 250-500 miles of running.(34) Since then, studies have actually demonstrated as absorptive qualities of a shoe are lost, the foot becomes more stable leading to the likelihood of reduced injury with more mileage.(35-37)

At the same time, the notion that runners with a high arch “need a great deal of shock attenuation because they don’t absorb shock naturally through pronation,” implies that we need to pronate to absorb shock. It becomes extremely crucial to look at pronation on terms of the entire foot as opposed to only the subtalar joint because more shock attenuation can be achieved utilizing the forefoot and midfoot.

Even if we consider implementing an orthotic into the shoe to control pronation, we have to consider the goal of this. The orthotic for an over-pronator is typically designed to control motion at the subtalar joint that results in increased pronation. With forefoot striking, we have to look at this from an entirely different perspective in which the orthotic would not serve the same purpose; therefore, its use is of question.

Landing

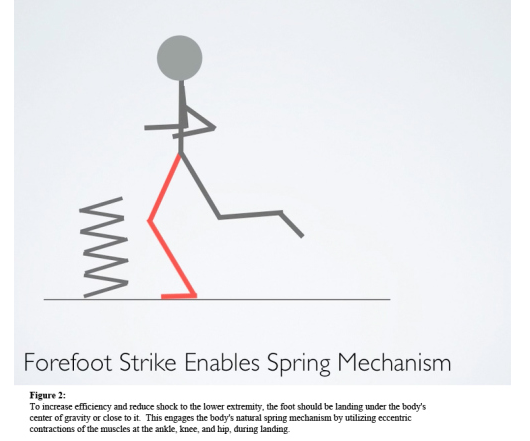

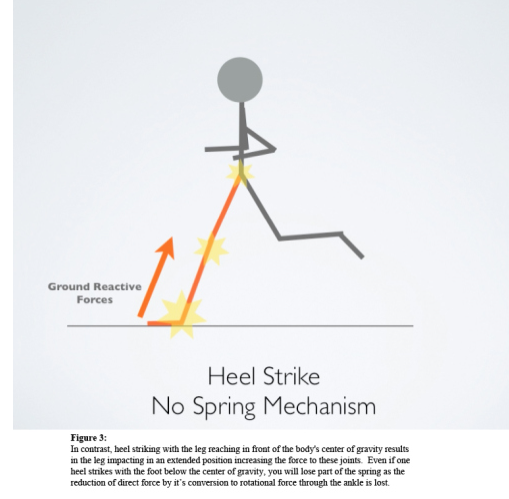

Where the foot strikes in relation to the rest of the body is also crucial. To increase efficiency and reduce shock to the lower extremity, the foot should be landing under the body’s center of gravity or close to it. This engages the body’s natural spring mechanism by utilizing eccentric contractions of the muscles at the ankle, knee, and hip, during landing (Figure 2). In contrast, heel striking with the leg reaching in front of the body’s center of gravity results in the leg impacting in an extended position increasing the force to these joints (Figure 3). Even if one heel strikes with the foot below the center of gravity, one will lose part of the spring as the reduction of direct force by

Where the foot strikes in relation to the rest of the body is also crucial. To increase efficiency and reduce shock to the lower extremity, the foot should be landing under the body’s center of gravity or close to it. This engages the body’s natural spring mechanism by utilizing eccentric contractions of the muscles at the ankle, knee, and hip, during landing (Figure 2). In contrast, heel striking with the leg reaching in front of the body’s center of gravity results in the leg impacting in an extended position increasing the force to these joints (Figure 3). Even if one heel strikes with the foot below the center of gravity, one will lose part of the spring as the reduction of direct force by  its conversion to rotational force through the ankle is lost.

its conversion to rotational force through the ankle is lost.

Cadence

Cadence is another piece to the puzzle. Cadence is the number of steps a runner takes per minute. Examining elite runners and marathoners, it has been determined that achieving a cadence of 180 steps per minute or higher will result in increased efficiency.(38) Running with a forefoot strike pattern makes it easier for one to increase cadence.(23) This high cadence keeps the runner closer to the ground reducing vertical motion that is associated with increased impact forces. (23) Shorter strides are associated with a higher cadence, but as speed increases the stride length will also increase.(23,27,32) It is important to understand that cadence should not vary with speed. For example, if running a 10 minute mile or slower, cadence should remain at 180 or greater. Faster paces such as 5:00 to 6:00 per mile can sometimes reach cadences of 200 or greater. The key is to understand that shorter strides and faster turnover will increase efficiency and reduce ground reactive forces.

Posture

Finally, the body’s overall posture also needs to be assessed. This can be somewhat confusing because some running

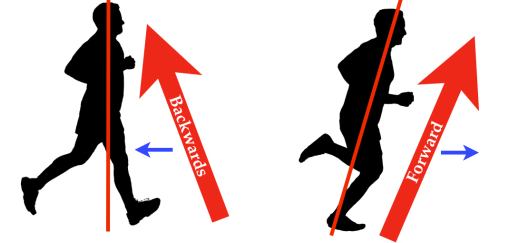

Finally, the body’s overall posture also needs to be assessed. This can be somewhat confusing because some running  instructors advise to keep an upright posture while others will advise to “lean forward.” Both are actually correct. The body’s overall position should be erect, but it should be falling forward. The term “leaning” should not occur at the waist such as bending over but the entire body should be angled forward (Figure 4). Running in place and then leaning forward to begin movement will help to teach this concept. This increases efficiency by utilizing forward momentum as opposed to decelerating with each step which recruits more musculature.

instructors advise to keep an upright posture while others will advise to “lean forward.” Both are actually correct. The body’s overall position should be erect, but it should be falling forward. The term “leaning” should not occur at the waist such as bending over but the entire body should be angled forward (Figure 4). Running in place and then leaning forward to begin movement will help to teach this concept. This increases efficiency by utilizing forward momentum as opposed to decelerating with each step which recruits more musculature.

Conclusion

Focusing on these steps discussed will help to improve a runner’s efficiency leading to reduced injury. New Balance has partnered with Kurt Munson, a well known running shoe retailer from Michigan, and created the educational concept known as Good Form Running.(18) Good Form Running teaches these steps in a simplistic manner, and specialty running shoe stores across the United States are holding clinics to instruct this.

Interestingly, children tend to run this way when they are unshod and playing outside.(39-41) The younger they are, the more noticeable this is as their gait has not been altered by wearing footgear. As for pediatric shoes, America Academy of Pediatrics recommends not wearing shoes until it is necessitated by the environment.(42) This helps to encourage natural foot motion, thereby enabling adequate development and strength gains.

A final point that is crucial in mentioning is training patterns. Most recreational runners and even elite runners tend to train too hard.(17) Improving the body’s aerobic capacity means to continuously train at an aerobic rate.(17) This is best achieved through the use of a heart rate monitor. Training too much at too high of a heart rate can lead to overuse injuries.(17) Runners too often focus on maintaining a pace instead of listening to their body and their training becomes borderline anaerobic.(17)

Obviously there is more to running than discussed here but having this, as a foundation, really helps anyone just beginning running or even those who have been running for many years. It is crucial for physicians treating running injuries to understand this.

In conclusion, it seems that most practitioners are straying from the path of helping a runner by focusing on shoes as opposed to form. The term “appropriate shoe” is a misnomer when viewed by the old paradigm of selecting a shoe according to arch type, and many are still advocating shoes this way. A running shoe should allow the foot to function as it was designed to – naturally without inhibiting motion. Adding cushioned heels and motion control mechanisms can inhibit this. By viewing shoes as the first line of treatment for most conditions, we must make sure this does not interfere with the foot’s natural function.

The shoe should feel comfortable initially (not with time) without a need for the foot to “get used to the pressure pushing against the arch.” A gradual adaptation to this way of running is obviously needed or injury can result as our feet and bodies may have been accustomed to a different form and supportive shoe. The approach is very similar to creating a program for someone just beginning to run.

References

1. Knapik JJ, Trone DW, Swedler DI, Villasenor A, Bullock SH, Schmied E, Bockelman T, Han P, Jones BH. Injury reduction effectiveness of assigning running shoes based on plantar shape in Marine Corps basic training. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Sep;38(9):1759-67. Epub 2010 Jun 24.

2. Clinghan R, Arnold GP, Drew TS, Cochrane LA, Abboud RJ. Do you get value for money when you buy an expensive pair of running shoes? Br J Sports Med. 2008 Mar;42(3):189-93. Epub 2007 Oct 11.

3. Butler RJ, Hamill J, Davis I. Effect of footwear on high and low arched runners’ mechanics during a prolonged run. Gait Posture. 2007 Jul;26(2):219-25. Epub 2006 Oct 20.

4. Kerr R, Arnold GP, Drew TS, Cochrane LA, Abboud RJ. Shoes influence lower limb muscle activity and may predispose the wearer to lateral ankle ligament injury. J Orthop Res. 2009 Mar;27(3):318-24.

5. Marti, B. (1998). Relationships between running injuries and running shoes—results of a study of 5,000 participants of a 16K run. The Shoe in Sport. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers. 256–265.

6. Herzog W. Running injuries: is it a question of evolution, form, tissue properties, mileage, or shoes? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012 Apr;40(2):59-60.Yeung SS, Yeung EW, Gillespie LD. Interventions for preventing lower limb soft-tissue running injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6;(7):CD001256. Review.

7. Yeung SS, Yeung EW, Gillespie LD. Interventions for preventing lower limb soft-tissue running injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6;(7).

8. Clinghan R, Arnold GP, Drew TS, Cochrane LA, Abboud RJ. Do you get value for money when you buy an expensive pair of running shoes? Br J Sports Med. 2008 Mar;42(3):189-93. Epub 2007 Oct 11. PubMed PMID: 17932096.

9. Gross ML, Napoli RC. Treatment of lower extremity injuries with orthotic shoe inserts. An overview. Sports Med. 1993;15(1):66-70.

10. Stackhouse CL, Davis IM, Hamill J. Orthotic intervention in forefoot and rearfoot strike running patterns. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2004;19(1):64-70.

11. Mattila VM, Sillanpää PJ, Salo T, Laine HJ, Mäenpää H, Pihlajamäki H. Can orthotic insoles prevent lower limb overuse injuries? A randomized-controlled trial of 228 subjects. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011 Dec;21(6):804-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01116.x. Epub 2010 May 12.

12. Kilmartin TE, Wallace WA. The scientific basis for the use of biomechanical foot orthoses in the treatment of lower limb sports injuries–a review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 1994;28(3):180-4.

13. Hohmann E, Reaburn P, Imhoff A. Runner’s knowledge of their foot type: do they really know? Foot (Edinb). 2012 Sep;22(3):205-10. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2012.04.008. Epub 2012 May 18.

14. Michelson JD, Durant DM, McFarland E. Injury risk associated with pes planus in athletes. Foot Ankle Int 2003;23(7):629–933.

15. Hespanhol Junior LC, Costa LO, Carvalho AC, Lopes AD. A description of training characteristics and its association with previous musculoskeletal injuries in recreational runners: a cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2012 Jan-Feb;16(1):46-53.

16. van Gent RN, Siem D, van Middelkoop M, van Os AG, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Koes BW. Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2007 Aug;41(8):469-80; discussion 480. Epub 2007 May 1. Review.

17. Maffetone, Philip. The Big Book of Endurance Training and Racing. Skyhorse Publishing. 2010 Sep 22.

18. http://www.goodformrunning.com

19. Edwards WB, Taylor D, Rudolphi TJ, Gillette JC, Derrick TR. Effects of stride length and running mileage on a probabilistic stress fracture model. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 Dec;41(12):2177-84.

20. Root ML, Orien WP, Weed JH. Normal and Abnormal Function of the Foot -Volume 2. Clinical Biomechanics Corp., Los Angeles, CA, 1977

21. Goss DL, Gross MT. Relationships Among Self-reported Shoe Type, Footstrike Pattern, and Injury Incidence. US Army Med Dep J. 2012 Oct-Dec:25-30.

22. Daoud AI, Geissler GJ, Wang F, Saretsky J, Daoud YA, Lieberman DE. Foot strike and injury rates in endurance runners: a retrospective study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 Jul;44(7):1325-34.

23. Lieberman DE, Venkadesan M, Werbel WA, Daoud AI, D’Andrea S, Davis IS, Mang’eni RO, Pitsiladis Y. Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature. 2010 Jan 28;463(7280):531-5.

24. Morley JB, Decker LM, Dierks T, Blanke D, French JA, Stergiou N. Effects of varying amounts of pronation on the mediolateral ground reaction forces during barefoot versus shod running. J Appl Biomech. 2010 May;26(2):205-14.

25. Eslami M, Begon M, Farahpour N, Allard P. Forefoot-rearfoot coupling patterns and tibial internal rotation during stance phase of barefoot versus shod running. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2007 Jan;22(1):74-80. Epub 2006 Oct 17.

26. De Wit B, De Clercq D, Aerts P. Biomechanical analysis of the stance phase during barefoot and shod running. J Biomech. 2000 Mar;33(3):269-78.

27. Robbins SE, Hanna AM. Running-related injury prevention through barefoot adaptations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1987 Apr;19(2):148-56.

28. Larson P, Higgins E, Kaminski J, Decker T, Preble J, Lyons D, McIntyre K, Normile A. J Sports Sci. 2011 Dec;29(15):1665-73. Epub 2011 Nov 18.

29. Hayes P, Caplan N. Foot strike patterns and ground contact times during high-calibre middle-distance races. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(12):1275-83. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.707326. Epub 2012 Aug 2.

30. Nigg BM. The role of impact forces and foot pronation: a new paradigm. Clin J Sport Med. 2001 Jan;11(1):2-9. Review.

31. Feltner ME, MacRae HS, MacRae PG, Turner NS, Hartman CA, Summers ML, Welch MD. Strength training effects on rearfoot motion in running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994 Aug;26(8):1021-7.

32. Ardigò LP, Lafortuna C, Minetti AE, Mognoni P, Saibene F. Metabolic and mechanical aspects of foot landing type, forefoot and rearfoot strike, in human running. Acta Physiol Scand. 1995 Sep;155(1):17-22.

33. http://www.asicsamerica.com/Shoe-Fit-Guide/

34. Cook SD, Kester MA, Brunet ME. Shock absorption characteristics of running shoes. Am J Sports Med. 1985 Jul-Aug;13(4):248-53.

35. Kong PW, Candelaria NG, Smith DR. Running in new and worn shoes: a comparison of three types of cushioning footwear. Br J Sports Med. 2009 Oct;43(10):745-9. Epub 2008 Sep 18.

36. Hamill J, Bates BT. A kinetic evaluation of the effects of in vivo loading on running shoes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1988;10(2):47-53.

37. Rethnam U, Makwana N. Are old running shoes detrimental to your feet? A pedobarographic study. BMC Res Notes. 2011 Aug 24;4:307.

38. Daniels J. Daniels’ Running Formula. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2005.

39. Wolf S, Simon J, Patikas D, Schuster W, Armbrust P, Döderlein L. Foot motion in children shoes: a comparison of barefoot walking with shod walking in conventional and flexible shoes. Gait Posture. 2008 Jan;27(1):51-9. Epub 2007 Mar 13.

40. Wegener C, Hunt AE, Vanwanseele B, Burns J, Smith RM. Effect of children’s shoes on gait: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Jan; 4:3.

41. Wolf S, Simon J, Patikas D, Schuster W, Armbrust P, Döderlein L. Foot motion in children shoes: a comparison of barefoot walking with shod walking in conventional and flexible shoes. Gait Posture. 2008; 27(1):51-9.

42. Hoekelman RA, Chianese, MJ. Presenting Signs and Symptoms. In: McInerny TK, Adam HM, Campbell DE (eds.) American Academy of Pediatrics Textbook of Pediatric Care, 5th edition, American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2.

The images contained in this article are borrowed from Dr. Campitelli’s interactive text, Running in a Minimalist Shoe and cannot be reproduced or borrowed without permission.

Dr. Nick, I have to say I think this was the best, most concise, and sensible discussion of minimal/natural running I have ever read – and referenced too!! It was like a textbook summarized in one article – well done and thanks for the good work which I will be sure to reference from in the future!

-John Andersen

Nick is one of the most experienced personally and professionally in this field. Thanks as always Nick for sharing your wisdom.

Mark

Great information. Now I finally know how or why my interior tibial tendon got torn and I am in severe pain now. But now that I know why it happened and what not to do once I am healed, how do I get healed in the first place? I have not been able to run or work out for about 2 years now, I wore a boot for 12 weeks, I have tried acupuncture, ice, compression socks, ice, epson salts, massage, laser therapy, supplements, physical therapy,orthotics…what do I do now? Do I start walking around in my bare feet as much as possible, or just try to walk on my mid to fore foot all the time, and in time the tendon will heal? How much longer do I have to wait?

Great information.

I’m a mid-foot striker and I was using New Balance minimalist shoes but started to have some achilles pain. During a fit in a shoes store they said I have high arch and overpronate and I needed a stability shoes instead.

Is it possible to use minimalist shoes if you have a high arch and overpronate ?

Thanks.

It’s great that you are getting thoughts from this post as well as from our argument made here.