The sub two-hour marathon is running’s final, most elusive barrier. The first runner to go 1:59 will become universally celebrated as marathon’s Roger Bannister. This timely book by Dr. Phil Maffetone, “1:59: The Sub-Two-Hour Marathon Is Within Reach—Here’s How It Will Go Down, and What It Can Teach All Runners about Training and Racing,” examines what it will take for an elite distance runner to go sub two hours.

The sub two-hour marathon is running’s final, most elusive barrier. The first runner to go 1:59 will become universally celebrated as marathon’s Roger Bannister. This timely book by Dr. Phil Maffetone, “1:59: The Sub-Two-Hour Marathon Is Within Reach—Here’s How It Will Go Down, and What It Can Teach All Runners about Training and Racing,” examines what it will take for an elite distance runner to go sub two hours.

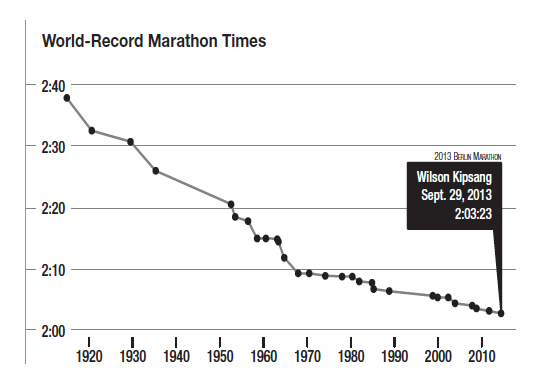

The current world record is 2:03:23. Wilson Kipsang, of Kenya, set it at the 2013 Berlin Marathon.Yet elite marathoners, mainly from Kenya and Ethiopia, seemed to have reached a plateau in running significantly faster. Why is that the case? Or better yet, what will it take to go sub two-hours?

“There are specific training and racing factors that are absolutely essential for going sub two hours,” writes Maffetone. “In addition to raw talent, optimal body size, and the right kind of athletic genes, the runner must follow a healthy diet and an individualized training regimen that takes advantage of specific environmental factors (“live high, train low”). Because precious seconds count over each mile run, other critical considerations include improved running form and economy, sharpened mental focus, and wearing the right type of racing flats (or even going barefoot).”

Maffetone is uniquely positioned to come out with this groundbreaking title. A longtime fixture, popular author, and coach in the endurance world (he closely worked with six-time Hawaii Ironman champion Mark Allen and running great Grete Waitz), he wrote the first book on heart rate monitoring (early 1980s), was the first to write a book about the importance of feet for athletic performance and going barefoot (late 1990s), and he’s now the first to write a book about the sub two-hour marathon.

In this except from “1:59” for the Natural Running Center, Maffetone looks at the meaning of time, VO2max test and their relationship to going sub-two hours in the marathon. As he writes, “Smarter, more efficient training may be just one of the reasons that we are now witnessing breakthrough marathon times.”

***

Training Time

One of the reasons why some physiologists, coaches, and athletes don’t rely on the traditional VO2max test—the maximal oxygen uptake—is time. During a VO2max treadmill evaluation, the runner is neither told how long to run nor miles necessary, only that he or she will continue running to exhaustion, or some maximum level.

Without this critical information, the brain does not know how to optimally proceed in making the body run; consequently, the test results are less valid.

Our running culture traditionally trains by miles or kilometers. Hardly anyone goes out for a workout without knowing beforehand, and with a fair degree of accuracy, how long a distance the run willbe. Specific mileage programs appear in magazines, are prescribed by coaches, and prepared by athletes as if running a certain number of miles means something very precise. It does not.

Our current race culture essentially does the same thing. Almost all events are promoted by a specific distance—5K, 10K, half-marathon,a marathon. Nervously standing or crouching, and maybe shuffling in place at the front of the starting line, elite runners intently focus on time. Many have their index fingers gently resting on their watches’ start button, waiting for the gun to go off. Midpackers do the same, as much focused on a precisely calculated and anticipated finishing time as anything else during the course of the race. (Stand near the finish line of a marathon, and you’d be surprised by just how many runners look first at their watches as they cross the finish.)

But independent of the timepiece and occurring deep inside the brain, all the miles are being mentally processed. It’s a natural for us to do that. The brain needs to know how much time it has to accomplish the task at hand. That’s because time is transcendent. It defines who and what we are.

As a coach, I always used time, and not miles, when writing up programs for my athletes. I found that many runners initially had difficulty adapting to my approach. Even when they were weaned off the notion of miles, they still wanted to refer to, say, a one hour run as going a certain number of miles. Often they kept these secrets to themselves, but in their diaries, which I often looked at, they were jotted down in minutes and hours. Finally, in order to make each timed workout much more meaningful, one’s heart rate should also be included in a training log. Simply writing down “ran seven miles” merely indicates how far the run was, and little more.

Smarter, more efficient training may be just one of the reasons that we are now witnessing breakthrough marathon times.These appear as personal bests by individual runners, with numbers that get lost in the dense fog of statistics. In 2011, Kenyan Patrick Makau

While many focus on the record being broken by “only” twenty-one seconds, it was a PR for Makau by a minute and ten seconds. American Ryan Hall, who had a relatively poor showing in the 2014 Boston Marathon, had run a personal best three years earlier on the same course by a minute and nineteen seconds (2:04:58). Just ahead of him was Ethiopian Gebre Gebremariam, who ran his all-time best by just over three minutes. We rarely see such significant breakthroughs in times during shorter events on this elite level, even those that are percentage-based, wind-aided, or on fast road courses.

Despite the statistician’s meta-analysis, whereby the trickle-down effect is used to show that marathon records are broken by some predictable pattern and usually not by very large differences, this is not always the case. Certainly there are several instances of marathon records being set in which a runner knocks down a huge chunk of time—thirty or forty-five seconds—from the previous world best. In1967, Australian Derek Clayton’s 2:09:36 was almost two-and-a-half minutes faster than the previous world best run by Japan’s Morio Shigematsu at 2:12:00 (1965). Looking back further, the U.K.’s Jim Peters ran 2:18:40 in 1953 to break his one-year-old marathon record of 2:20:42. The previous record was 2:25:39, run by Korea’s Suh Yun-bok in 1947—making Peters’ world-best margin seven minutes and change, or about five percent.

A more accurate gauge of the progression of world-record times is by looking at percentage improvements. To run 1:59, a runner would have to break the current world record by 3.2 percent, and even less using Geoffrey Mutai’s unofficial Boston marathon record.(If 1:59 is someday recorded at Boston, so be it.)

Those of us who run in marathons usually think of time as a factor that continuously works against us, and it certainly can have that psychological effect. But as history has clearly shown, there is no running event in which the times don’t go faster. Whether it’s 100meters or 26.2 miles, records will continue to be broken. This reflects an inevitability that’s deeply rooted inside human nature. We thrive on competition and the ceaseless need to outshine the past. We want to stand apart from our rivals by being the best at something. Once a runner finally makes it to 1:59, expect to see other runners immediately rise to the challenge and attempt to go even faster.

Buy book here: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1629148172/ref=cm_cr_ryp_prd_ttl_sol_0

thanks Phil and Bill for sharing this book which lends critical insight into optimal health, not just fast marathons. Mark