Pete Larson, aka Runblogger and Natural Running Center science advisor, has recently written an essay that he calls “a giant brain dump” on Vibram Fivefingers, barefoot running, shoes, heel strikes, loading rates, and injury risk. Most of that article is reposted here. Thanks Pete for allowing our readers access into your big scientific brain. –NRC

The American Council on Exercise (ACE) has been taking the shoe industry to task recently. Several months ago they put toning shoes to the test, finding that claims of increased muscle usage and calorie burn are not substantiated when tested in the laboratory. Here’s an excerpt from the ACE toning shoe study:

“Across the board, none of the toning shoes showed statistically significant increases in either exercise response or muscle activation during any of the treadmill trials. There is simply no evidence to support the claims that these shoes will help wearers exercise more intensely, burn more calories or improve muscle strength and tone…”

In other words, they put the marketing claims by the shoe manufacturers to the test, and they don’t stack up to the science.

Yesterday, ACE released findings of a study of another red hot footwear trend. Specifically, they published results of a study that examined how running in the barefoot-style Vibram Fivefingers shoes compares to actually running barefoot, and to running in a typical cushioned running shoe.

The design of the ACE study was simple and straightforward. Researchers at the University of Wisconsin La Crosse recruited 16 healthy female runners to participate, and they provided each subject with a pair of Vibram Fivefingers Bikila running shoes. The subjects were allowed two weeks to acclimate to the shoes, and were instructed to run in them 3 times each week for up to 20 minutes on each occasion (or until discomfort occurred – I personally would advocate for an much slower ramp-up than this). After the two week acclimation period, the subjects were brought into the laboratory and they ran across a force platform under three footwear conditions (7 times in each condition): 1) barefoot, 2) in Vibram Bikilas, and 3) in neutral cushioned shoes (New Balance 625). Both kinematic (e.g., joint angles) and kinetic (force) measurements were made for each running trial.

Focusing first on kinematics, the results of the study indicated that all 16 individuals were heel strikers in the New Balance shoes. However, when barefoot or in the Vibram shoes, about half of the individuals switched to a forefoot strike landing pattern with greater plantar flexion of the ankle at the moment of ground contact. Additionally, regardless of foot strike type, the subjects exhibited less total knee flexion during stance when running barefoot or in Vibrams than when they were wearing the NB shoes (so form did change in some ways, even if foot strike pattern did not). When compared to both shod conditions, barefoot runners exhibited less pronation (I love this little nugget of data!).

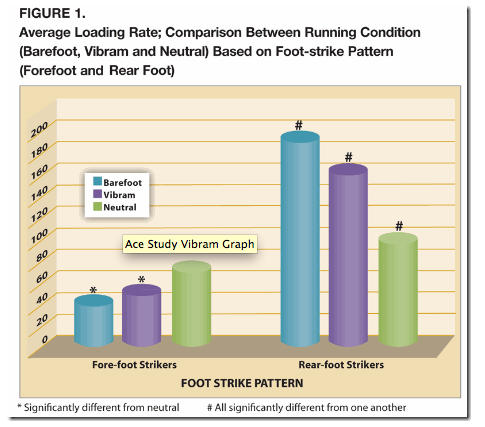

With regard to kinetics, the researchers honed in on vertical loading rates – loading rate refers to how fast the foot impacts the ground (for more on this,read this post on loading rates). There is some debate about whether loading rate is a good predictor of the likelihood of suffering a running injury, but there exists evidence for at least an association between vertical loading rate and risk of certain types of stress fractures. Results of the ACE study indicated that forefoot strikers exhibited lower mean loading rates than heel strikers (see graph below). Among forefoot strikers, loading rates were significantly lower when the runners were barefoot or in Vibrams than they were when they were wearing the neutral cushioned shoes. The opposite pattern held for heel strikers – loading rates were significantly higher when barefoot or in Vibrams. Another way of saying this is that the cushioned shoes produced the lowest loading rates of the three conditions for heel strikers, but the highest loading rates for forefoot strikers.

So what does all of this mean? Well, first, it should be noted that this is not an article published in a peer reviewed research journal, so it’s difficult to evaluate it in full detail. However, given the information provided, what I find really interesting is that the results show that when you put an individual into a shoe like the Vibram Fivefingers, there seems to be only about a 50% chance that they will stop heel striking on their own.

This matches closely the results of an acclimation study conducted by Daniel Lieberman, where he found that 7 of 12 individuals who were initially midfoot or heel strikers switched to a forefoot strike after 6 weeks of running in Vibram Fivefingers. The results of the ACE study also match my very rough estimate of the percentage of the Vibram Fivefingers runners who were heel striking at the NYC Barefoot Run last Sunday (barefooters seemed to be much more likely to forefoot strike).

If the data presented here are correct, and that any form of heel strike when barefoot or in a minimal shoe like the Vibrams will dramatically increase loading rate, then individuals who continue to heel strike when barefoot or in the Vibrams may be at risk (if in fact loading rate increases injury risk). Personally, I’d like to see data on if/how vertical loading rate varies with foot contact angle, knee flexion, and distance of contact from the center of mass among the heel striking runners. Is it possible to run barefoot or in Vibrams safely with a heel strike? Maybe, perhaps if an individual is strong and other aspects of their mechanics are good. It’s also worth noting that even if loading rate is a risk factor for injury, that does not mean that if you have a high loading rate, you are guaranteed to get hurt. It’s merely an association, and some individuals may be able to tolerate a high loading rate better than others.

Perhaps what I find most interesting from the ACE study, as well as the film I have from the NYC Barefoot Run, is that it suggests that old habits can be hard to break. Your body learns how to run at a very young age, and most of us have done so with shoes on our feet (probably stiff or heavily cushioned shoes). When you look at Daniel Lieberman’s data for Kenyan kids who have never before worn shoes, they either midfoot or forefoot strike 90% of the time when barefoot. What would happen if they put on a pair of Vibrams? I don’t know, but it would be fascinating to find out. I’m doubtful that they would start heel striking.

My personal hypothesis is that we develop the specifics of our running form early in life, and what that running form looks like is influenced by our childhood footwear. I’m watching my 18 month old son learn to run right now, and some of his playmates are already in big, bulky running shoes. Once we start our childhood path in athletic shoes, it rarely deviates from the heel-lifted, heavily cushioned variety. As adults, we get to a point where some of us decide to take off our cushioned trainers (perhaps out of a desire to shed an injury, or simply due to curiosity) and try out a pair of minimal shoes like Vibrams. We expect miracles to happen, and, indeed, some of us switch our foot strike immediately and old injuries seem to disappear, probably due to altering individually problematic patterns of force application to our feet and legs. However, others (as many as 50% if the numbers are correct!), for whatever reason, do not. Why? That, to me, is the big question.

I think there is probably a big motor learning component here, and though some form adaptations (e.g., joint angles) may occur instantaneously, wholesale changes to highly ingrained movement patterns may just be hard for some people to accomplish. I’m not a psychologist, and my attempt to discuss motor learning variability with a colleague in the Psych Dept. upstairs from me led me to realize I have a lot of reading to do. The disparity in response among individuals to altering footwear condition fascinates me. For those who don’t switch right away, could form change be facilitated via cueing and coaching? Perhaps, and studies of real-time gait retraining have been shown the technique to be effective.

I also think it’s worth considering that a barefoot/Vibram heel strike may not be a bad thing for some people. Before you accuse me of being crazy, read this conference abstract. Based on the results reported in the abstract, it appears that different people adopt different strategies to reduce tibial shock. Some adopt a midfoot/forefoot strike, whereas others use an “ankle strategy” with greater dorsiflexion and decreased knee flexion at foot strike. I can’t tell from the abstract if these individuals were wearing shoes, but I suspect that they probably were, as a heel landing with extended knee would not seem to be an effective way to reduce tibial shock without some amount of cushion under the heel. However, this could explain why so many people in cushioned shoes seem to overstride. Amby Burfoot asked Irene Davis about these somewhat counterintuitive results, and here is what she had to say:

“Runner’s World: In one of your form-changing studies, you apparently found that runners could reduce tibial shock by either landing more on their midfoot or forefoot, or by landing further back on their heels. Those results seem sort of contradictory.

Irene Davis: Indeed, Brad Bowser, lead author, and I were surprised to see the increased rearfoot strike. We had hypothesized that they would reduce the tibial shock by transitioning to more of a forefoot landing. But we didn’t instruct the runners how to reduce their loading – we allowed them to adopt their own strategy as we were interested in how they would do it. And it appears that more runners adopted the greater rearfoot strike pattern.

Here’s what I think happened: I think most of them utilized the rearfoot strategy as it was their accustomed pattern. Instead of changing to a midfoot or forefoot strike, they just accentuated it more and sort of rolled through their foot strike.”

Echoing Davis’ comments, here is a statement from Dr. John Porcari, who was one of the authors of the ACE study discussed in this post:

“It’s tough to re-learn to run,” says Dr. John Porcari. “When you look at the data even though we encouraged them to run with a more forefoot strike while wearing the Vibrams, half of the subjects still continued to land on their heels. Even with two weeks to practice and instruction in how to use the barefoot shoes, [the subjects’] bodies still tended to run the way they’ve always run.”

“It’s tough to re-learn how to run.” That quote really sums it up, but I would qualify it by adding “for some people.” Nonetheless, when I ponder this, I keep coming back to the fact that we really need to start with the kids. Get them in good shoes from the start. Let them develop the strength and internal stability that they need to support their ability to run. Let them develop their “natural” running form free from the influence of overly controlling, cushioned, and supportive footwear. Let them run barefoot when they want, so that they can develop their proprioreceptive abilities. Encourage activity, not just in childhood, but throughout life. If we did this, we would not need form coaches, and I honestly believe we would all be a lot better off.

This debate is not so much about being barefoot or being shod – the fact of the matter is that most people are going to wear shoes when they run. The focus should really be on running well, being strong, building internal stability, and naturally developing the form that is most appropriate for your individual body structure. We may not all wind up running the same way, but I truly believe that each of us has a form that will work best for us on an individual level. That “best form” may be your current form, or it may not. It may take a bit of experimentation, practice, learning, and yes, perhaps even a bit of coaching to find it. The end goal, though, is to be able to run – nothing more, nothing less – and I think that is something that we can all agree upon.

Go here to read Pete Larson’s essay in full.

Nice article Pete. This is what I see (they heel strike) for a majority of patients who run barefoot on the treadmill when I evaluate them. I give them no guidance, but just run at a self selected speed. I was a little surprised it was this high when I looked back at the data. Although it was less of a heel strike barefoot compared to the running shoe as cadence increased when barefoot. I suspect landing on the heel would much lower on concrete or asphalt. This points the fact that with our recommendations on footwear or lack of footwear; we need to “coach” running change if it is needed.

Thanks Roberto,

Without science data but like you with lots of personal and runner experience i think it is safe to say you can heel strike pretty comfortably on the treadmill (most have some cushioning). But on concrete….not really. We still do not know how all this relates to future injury risk as there are lots of things happening in the running gait beyond the landing pattern.

Mark

After I paused for several years, I started running again half a year ago. It took me many weeks to develop a decent forefoot/midfoot- strike, but now the mechanics works as if I had never run differently. It’s a lot more fun, too.