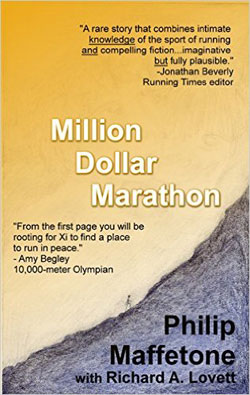

The first work of fiction from Phil Maffetone: Million Dollar Marathon. It’s a novella (aka short story) that is now available on Amazon Kindle.

The first work of fiction from Phil Maffetone: Million Dollar Marathon. It’s a novella (aka short story) that is now available on Amazon Kindle.

When Xi, a shepherd from one of the most remote parts of Tibet, flees across the Himalayas to India, he doesn’t know what awaits. But his very act of fleeing—alone and on foot—demonstrates a unique skill.

In Tibet, Xi had barely heard of the marathon, never raced against anyone other than himself. Now, with the help of the mysterious Mr. Singh, he sets out to do what nobody has ever done before: break 2 hours for the marathon—all while remaining true to who he is and where he came from.

Testimonials

“A rare combination of intimate knowledge of running and compelling fiction…imaginative but fully plausible.”

—Jonathan Beverly, Running Times

“From the first page you will be rooting for Xi to find a place to run in peace.”

—Amy Begley, 2008 Olympian

“A joy to read for any runner, not just marathoners. I found my heart racing at the end. I couldn’t put it down.”

—Lt. Amanda Rice, U.S. Navy, 2:38 marathoner, 2014 military division cross-country champion.

Sample Chapter

Chapter 1 – Xi

Dawn comes slowly in the highlands near the Tibet/Nepal border. It begins with a gradual gathering of light as hints of radiance, invisible from below, are caught by Himalayan snows still far removed from seeing their first true kiss of sun. Stars shine undimmed and only the night-adapted eye knows the darkness will soon end.

But as slowly as the night was changing, it was changing too quickly for Xi. If he could, he would have held back the dawn by sheer force of will. He had always known this was the most dangerous part of his journey and he had hoped to get here in the middle of the night, not at dawn.

Hiding and waiting for tomorrow was not an option. By then, his absence from the village would certainly be noticed. By then, people would be wondering why he hadn’t brought his flock back from pasture. Nobody stayed alone in the mountains that long. Soon people would go looking for him and when they found his animals with no trace of their shepherd, it wouldn’t take them long to figure out where he had gone. Most wouldn’t care—many would wish him luck. But there would be someone who would find advantage in reporting him, and once that happened, the border would be alerted and his chances of getting across significantly reduced. Perhaps someone had gone looking for him yesterday and he had already been reported. If so, his main hope would be that few would imagine he could have gotten this far, this quickly. Tomorrow night the border guards would be looking for him. Tonight, he still had the advantage.

Xi had hiked, run, and scrambled the mountains since before he could remember. But he had never before had reason to climb this high. And while his breathing was heavier than he was used to, it was a comfortable exertion. He could go on at this rate for hours—had done so many times in the past, roaming barefoot though the meadows where his sheep now rested. If asked back then, he would have said he was looking for predators, as he had been shown by his grandfather, who had been taught by all the generations of shepherds before him. But predators were becoming rare in modern Tibet and mostly, Xi had been running for the simple joy of movement…and practicing for the escape that would soon either work or leave him dead.

Years ago, when Xi was on one of his rare visits to one of Tibet’s larger cities, a merchant had noticed his bare feet and managed to shame him into buying shoes that were supposed to help him run farther, faster—strange, bright-colored footwear made in a far-off factory in some place like Shanghai, Tianjin, or Shenzhen. But shoes were something he only wore when the alternative was frostbite and even then he preferred moccasins. The shoes had not only cost too much, they’d pinched his feet and made him hobble when he tried to run. Barefoot he had come into this world, and barefoot he would leave it. He just hoped the leaving wouldn’t come soon at the end of a border guard’s gun.

He quickened his pace. The pass above wasn’t a place anyone he knew had actually seen, but it was up there somewhere. The terrain was steep but did not require the type of mountaineering equipment foreign tourists sometimes carried to the icy peaks above his own high pastures—summits that beckoned them the way the border now called to him. Maybe he could still make it before dawn.

Xi was a shepherd from a long line of shepherds. From far before the memory of anyone living, his ancestors had jogged their flocks to the highest pastures in Central Asia. Some said his people originated in what was now Mongolia; others said they found their way across the high Tian Shan, which separated modern Tibet from the lands to the west. Perhaps the exact “where” didn’t matter. What did matter was that they had lived in the highlands since time immemorial.

Then, when his grandfather was young, the Chinese came with their horses and horse soldiers and Cultural Revolution. Thousands died and Xi’s grandfather had had many experiences he’d refused to talk about. “Learn to run and never quit,” was all he would say. “Horses are faster, but only if they catch you in the open. If you can run the mountains, you can escape. But even as a child, Xi knew the Chinese were too strong ever to resist again that way. His grandfather, though, never forgot the old days, never quit reminding not only the villagers of his own clan but neighboring ones of the freedom they had lost. When Xi was fourteen, horse soldiers rode through the villages and his grandfather was never seen again. Had he escaped or discovered that however fast he’d been in his youth, bullets were faster?

Education was supposedly compulsory in the New Tibet, but putting food on the table was even more compulsory. Xi’s parents had died when he was young, and when his grandfather disappeared he learned how to avoid school to tend the sheep. But he was curious, and in the high meadows he found the best of both worlds. Often, he took one of his grandfather’s old books—sometimes a prohibited one, sometimes not. Books were tightly controlled in the New Tibet, but his grandfather had somehow acquired a number of them and had shown him how hide them if necessary.

Back in the villages, tourists from far-off places increasingly came and went: places like Sweden, Japan, Australia, Germany, and Russia. Some came to climb, some just to take pictures or play at being Buddhist—a religion Xi’s own people had never adopted.

The books Xi carried to his high pastures covered science, language, history, geography, arts, and anything that interested him. Religion and philosophy weren’t among them. He didn’t care about Buddhism’s shrines and mysticism; he only knew he belonged to the natural world and that living and moving in it meant joy—and that joy…not pleasure but delight…was the key to truly being alive. The only person who could determine what gave him joy was he, himself. The monks in their colored robes and incensed prayer houses paled in comparison to running free through the high meadows.

Meanwhile, the tourists expanded his worldview even more than the books. Before his grandfather disappeared, he would have been hard pressed to locate Sweden on a map. Then one of the tourists gave him a Swedish/Chinese phrase book. Tibet itself had a half-dozen languages, not including those brought in by the Chinese. Xi didn’t speak them all but had long ago discovered that the more languages he knew, the easier it was to learn more. Soon enough he’d learned Swedish. Soon after, he realized that almost all of the tourists spoke an even more useful language, English.

There were days when he did not want to read. Those were the ones when he ran simply for the sake of running, in

a symphony of footsteps, breath, and heartbeat. On those days, he also sang. Singing, his grandfather had taught, kept the wolves at bay—though Xi couldn’t remember the last time anyone had seen a wolf. One of the prohibited books said there were only a few hundred left. Perhaps, just as they had conquered his own people, the Chinese had also conquered the wolves. It was the type of thing they would do in their unending quest to “improve” the Old Tibet his grandfather had known.

The songs and books taught different stories. The books said his people dated back only a few thousand years. The songs said everyone on Earth originated from them. Xi wasn’t sure which was right. One of the things he’d learned was that people all over the world believe they are the best at something. In fact, when it came to the people of Tibet, even the Chinese might agree. When Xi’s grandfather was still alive, they had come to the mountains looking for runners, trying to recruit them for the glory of the People’s Republic. A few accepted. Others resisted, only to have the money forced on their families as “compensation.” Some of the villagers had briefly talked of recruiting a team to run under the multi-hued sunburst banner of Tibet’s one-time national flag, but their leaders soon disappeared as completely as Xi’s grandfather.

The Old Tibet was gone; the New Tibet was increasingly Chinese. Xi did not want to be assimilated. Not only did the old songs teach that his people had their own history, but he was too much his grandfather to simply surrender to the changes. He had been studying languages and reading prohibited books for two decades. He had no spouse, no children; the time had come to leave.

The air was getting thin even for Xi, and there was still no summit in sight.

The highest formal trail across the Tibet/Nepal border lay at an elevation of 5,800 meters but too many people had died trying to sneak across it. Xi’s pass was not quite as high but harder to reach and less likely to be as well guarded. There were even harder-to-reach passes, but for them he’d need mountaineering equipment, specialized training, and help. He preferred to rely on his own strengths, starting with his ability to run with only the lightest of packs. Assuming, of course, he reached the pass before the approaching daylight made him an impossible-to-miss human dot on a vast expanse of snow.

Back in his village, Xi didn’t own much, but he’d had enough to be comfortable. Now, the ten kilos in his backpack were all he had left. He’d spent weeks picking out what he would carry. A few small gold coins plus what little cash he’d been able to scrape together without attracting attention. Food and a water bottle he periodically refilled with snowmelt. Extra clothing plus his best lambskin moccasins for the cold. A small, framed photo of his grandfather. A copper teapot that had been in his family for generations and an entire kilo of the leaves of a plant he knew as Tara, along with three Tara bulbs sealed in a small plastic bag.

Xi had read that the English and Chinese drank tea. Others drank coffee or beverages unknown in Tibet, such as tej, the home-brewed honey-wine favored by Ethiopians, or coconut arrack, the fermented palm-sap drink enjoyed in Sri Lanka. Xi’s people drank Tara. It grew only in terrain too rugged even for most Tibetans. Picking and brewing it, his grandfather had taught him, was part of what it meant to be one of his people.

Not that Tara was unknown outside of Tibet. Traders from Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and other places had long claimed it had miraculous healing powers. And while Xi thought its greatest value lay simply in the soul-centering ritual of brewing and drinking it, others had been willing to supplement their incomes by selling it to the Chinese. As the price soared, the herb became harder and harder to find, but Xi’s grandfather had taught him how to find it among rocks where little else grew, and Xi himself had found patches unknown even to his grandfather. Still, it was rare enough that he never harvested more than he needed.

When he finally reached it, the border was anticlimactic. By then, the snow was knee-deep and Xi’s pace had slowed to a crawl. Above, serrated peaks rose in cliffs and fluted columns. But if there were guards, they were so well hidden Xi couldn’t spot them, even though the dawning light was now bright enough to make him feel like a fly under a spotlight. Perhaps they were all still asleep under the influence of… well, whatever it was the Chinese guards drank. The Kazakhs, who had a lot more in common with Xi’s ancestors than did the Chinese, drank fermented mare’s milk. Xi avoided even beer. Tara was all he needed.

Wherever the Chinese were, or whatever they’d been doing, they weren’t watching him. Still plunging through the snow, he crossed a broad, flat expanse and began to descend into Nepal. Two days later, he slipped across another border, into India.

He wound up in a Tibetan refugee camp in the hill country of eastern Uttar Pradesh, where his new country offered safe refuge, food, and a bed in exchange for work. But it wasn’t the type of work he was used to, roaming free in the hills. Here, he was working in the fields—active but always in the same place, day in and day out. There were no high pastures to climb to, no reason to run singing through the mountains. Only dirt, dust, and rice.

Within a week, he’d recovered from his flight up and over the Himalayas. By the second week, he was feeling confined, surrounded by too many people. Early in the third week, he woke before dawn and went for a two-hour run, exploring the countryside around his camp. Within minutes, he felt a peace he’d not felt since his decision to leave Tibet. Movement…and singing. Those were the keys to balance, to facing the unknowns of his new life. Singing not only brought joy, it helped him run. Balance was life. Everything else just happened along the way.

A few days later, Xi crested a hill and discovered he was not the only runner on the red-dust roads surrounding his refugee camp. Ahead was a small group of others, dressed in bright-colored shirts that danced in the heat-shimmered distance like faraway prayer flags. Even though it was time to turn back if he wanted to get back to the camp in time for breakfast, Xi gave chase, fascinated by the other runners’ tight pants and shirts, made from less material than it would take to clothe a baby. Closer yet, he realized they were wearing shoes in color patterns even more fanciful than their clothing.

“Good morning,” he said in English, as he drew close to the trailing runner.

“Whunh?” the Indian said, nearly tripping as he looked back. “Where did you come from?”

Tibet, Xi almost replied, then realized that wasn’t what the runner meant. He had forgotten that bare feet are quieter than shoes and in his fascination with the other runners, he had quit singing. “I first saw you”—he began, then paused, calculating…maybe three or four kilometers back. It took me until now to catch you.”

The other runner gave him an odd look. “In pants? And long sleeves? Barefoot? I went to university in America. Running paid for my education. Even on an easy day, nobody can catch me that way.”