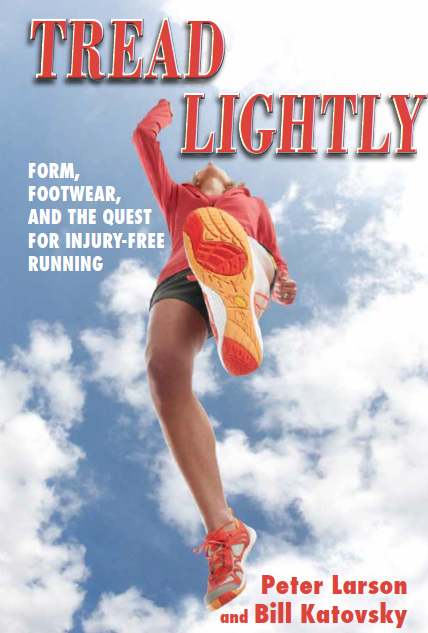

In the new book. Tread Lightly: Form, Footwear, and the Quest for Injury-Free Running, Dr. Peter Larson (Runblogger) and Bill Katovsky (Natural Running Center co-founder and editorial director) explore the reasons why pain is so frequently a part of the life of the modern runner, and search for potential solutions to the ongoing injury epidemic. Could it be the shoes? Running form? Even diet? Tread Lightly arrives at a pivotal time as the running world is in the midst of a revolution. Runners everywhere have begun to move away from the big, bulky, and extra-cushiony shoes that have filled store shelves for decades. Many runners have even gone so far as to experiment with barely-there minimalist footwear or barefoot running in an attempt to overhaul their running form in an effort to escape injury. In the process, some have seen chronic injuries disappear, while others have developed new problems in their attempt to run in a barefoot-like style. Tread Lightly addresses these topics. The book can be purchased on Amazon. Go here. The following excerpt is from the chapter “The Recreational Runner.” –NRC

In the new book. Tread Lightly: Form, Footwear, and the Quest for Injury-Free Running, Dr. Peter Larson (Runblogger) and Bill Katovsky (Natural Running Center co-founder and editorial director) explore the reasons why pain is so frequently a part of the life of the modern runner, and search for potential solutions to the ongoing injury epidemic. Could it be the shoes? Running form? Even diet? Tread Lightly arrives at a pivotal time as the running world is in the midst of a revolution. Runners everywhere have begun to move away from the big, bulky, and extra-cushiony shoes that have filled store shelves for decades. Many runners have even gone so far as to experiment with barely-there minimalist footwear or barefoot running in an attempt to overhaul their running form in an effort to escape injury. In the process, some have seen chronic injuries disappear, while others have developed new problems in their attempt to run in a barefoot-like style. Tread Lightly addresses these topics. The book can be purchased on Amazon. Go here. The following excerpt is from the chapter “The Recreational Runner.” –NRC

***

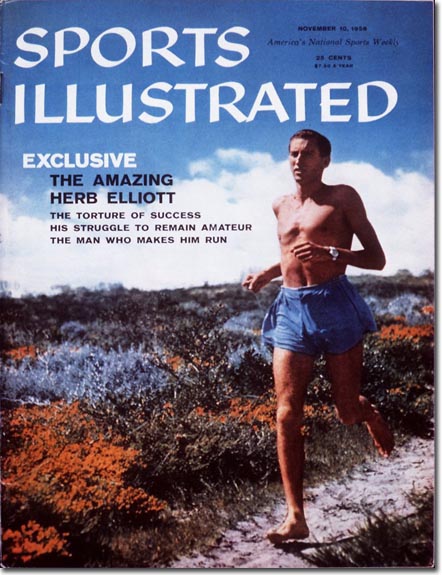

The sixties began, curiously enough, with an anti-shoe bias among a distinguished roster of champion runners. We all know about the unshod Abebe Bikila whose bare feet flew over the cobblestones en route to winning the marathon at the 1960 Rome Olympics. (The Ethiopian runner wasn’t the first marathoner to go barefoot in the Olympics; that honor belongs to South African Tswana runner Len Taunyane, who finished ninth at the St. Louis Games in 1904.) Fewer of us are probably familiar with the serial accomplishments of Herb Elliott, a talented Australian middle-distance runner who appeared twice on the cover of Sports Illustrated, in 1958 and 1960, each time running barefoot! Elliott held the world record in the mile (3:54); and at the Rome Olympic Games, he won the gold medal in the 1,500 meters and bettered his own world record with a time of 3:35.6. He trained under the tutelage of his iconoclastic coach, Percy Cerutty, who embraced a mind-body, holistic approach to training that was centered around barefoot runs on the beach and sand dunes, discussing poetry and philosophy for mental stimulation,avoidance of wheat flour, and no water or liquids during meals.It also helped that Elliott possessed a graceful, natural running stride. From 1957 to 1961, Elliott was the preeminent middle-distance runner in the world. During this four-year stretch, he never lost a 1,500-meter or mile race.

Known as “Europe’s Barefoot Champion,” England’s Bruce Tulloh won the European 5,000 meters championship in 1962 by racing unshod on the cinder track. Tulloh had started running barefoot three years earlier because he was convinced that shoes were slowing him down. In short order and without shoes cramping his style, Tulloh won his first British amateur title barefoot and continued racing and setting U.K. records, including the two miles in 8:34, until he retired from competition in 1967.Two years later, he ran across the U.S. in sixty-four days—but he wore shoes due to his uncertainty about road conditions. Tulloh, seventy-six, who lives in Marlborough, England, went on to coach many top British middle-distance runners, authored several books on running, including a popular one called Running is Easy. He even spent a short spell in the early 1970s in Mexico’s Copper Canyon with the Tarahumara Indians and, like others who have had that opportunity, was amazed by how far and effortlessly they ran in their huaraches.

In 1961, Tulloh, who later became a biology instructor at a small British college for twenty years, was briefly placed under the microscope by a famous medical researcher interested in barefoot running. Dr. Griffith Pugh, who achieved fame as medical leader of the 1953 Everest climbing team, tested Tulloh on the track. In a 2011 interview with Running Times, Tulloh described the process: “Dr. Pugh had me run repetition miles, to compare the effect of bare feet, shoes, and shoes with added weight. He collected breath samples. It showed a straight-line relationship between weight of shoes and oxygen cost. At sub-5:00 mile pace, the gain in efficiency with bare feet is 1 percent, which means a 100 meter advantage in 10,000 meters. In actual racing, I found another advantage is that you can accelerate more quickly.”

Barefoot racing was also popular among other elite British runners, such as Ron Hill, who ran barefoot when he took second in the International Cross-Country Championship in 1964. The following year,the shoeless endurance athlete won the Beverley (England) Marathon, in 2:26:33. At the Mexico Olympics, he placed seventh in the 10,000 meters—again without shoes. Hill also told Running Times, “I was going to run the marathon at the 1972 Munich Olympics barefoot, but the Germans laid new stone chippings on parts of the course.”

In the United States, Dale Story, a junior at Oregon State, won the 1961 NCAA cross-country championship by running barefoot. In a recent interview with an Oregonian newspaper, he reminisced, “People laughed at me. There were acorns on the course. Those guys thought I was absolutely crazy. They said, ‘Man, you’re going to hurt your feet.’ Didn’t bother me at all.”

Given the fact that these highly accomplished runners—Bikila, Elliot, Tulloh, Hill, Story—had achieved success without shoes, then why didn’t more of their contemporaries take up barefoot running? One likely reason might have had to do with perception and habit. Perhaps there was something retrograde, an anti-modern reversal of the natural order of things, about barefoot running that made it seem far too primitive to have any real appeal for almost all westernized runners at the time. Or maybe it was due to practical concerns like having one’s unprotected feet encounter broken glass, sharp objects, or unwanted debris. These are all legitimate considerations that continue to resonate today among runners.

But in the early 1960s, there was something else standing directly in the path of barefoot is best. Quality running shoes designed specifically for road racing and training had finally begun to appear—not in mass quantities by any means, but in limited numbers. Runners looking for that competitive edge were drawn to Tiger Cubs that were manufactured by Japanese-based Onitsuka. The lightweight Tigers had flat-bottom rubber soles, were easy on the feet, and held up pretty well. They could be purchased via mail order for the discerning few. Demand was still quite small because running was very much a fringe sport attracting only the diehards.

“The 1960s,” says runner Hal Higdon, who went onto become a well-known author and contributing editor for Runner’s World, “was a decade both dark with despair and bright with hope, an era when the Boston Marathon attracted only a few hundred starters, most of them capable of breaking three hours. Nineteen fifty-nine was the year I ran my first Boston. We were a scurvy lot, the 150 of us who showed up in Hopkinton, our deeds largely unheralded.” At least, this small, nearly invisible group of malnourished American and British long-distance runners now had the option of running in decent shoes.

***

Buy Tread Lightly. Go here.