by Roman Urbina, Race Director of La Ruta Ultra Run.

The Tarahumara have this wonderful expression that I learned to appreciate after recently spending several days with them, the first time in Costa Rica last November and the second occasion recently in Mexico. Both times centered on 100-kilometer running events, each one incredibly difficult and challenging in its own way. The word is “korima” which translates into ¨share¨ or ¨sharing.” It describes how the Tarahumara share food, songs, laughter, hardships, family, running, life.

So let me begin this personal essay by saying I too want to share my experience of what it was like running and hanging out with these remarkable people. As a result of Chris McDougall’s international bestseller Born to Run, these shy, poor, and reclusive indigenous people who live in the northern Mexico state of Chihuahua, specifically in the remote Copper Canyon, have come to change the way many runners now look at their own biomechanics when running.

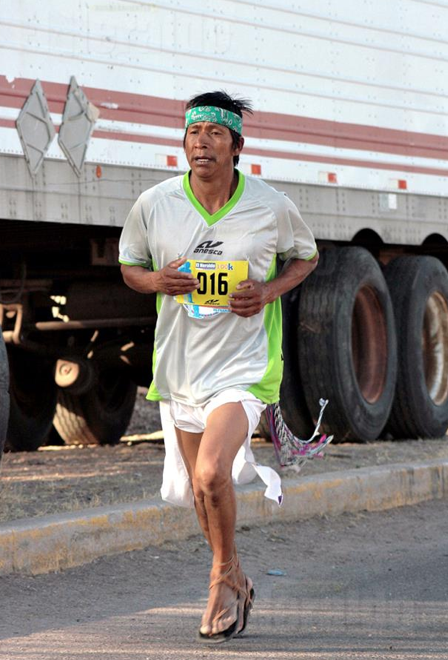

Despite the widespread encroachment in Copper Canyon of deforestation, logging, mining, and an expanding drug trade that’s threatening to imperil their traditional way of life, these huarache-wearing endurance warriors have also shaken up the multi-billion dollar footwear industry. For the past several years, an increasing number of shoe companies have been manufacturing barefoot-style and minimalist running shoes for the masses. I read somewhere that it’s almost 10 percent of all running shoes sold. But there’s also a great deal of irony associated with this phenomenon: most of the 100,000 Tarahumara are totally unaware of their global impact on running today. Nor do they crave or want the attention or publicity. They run because that’s who they are. Their real name is Raramuri– an indigenous word that means “light feet,” as in fast running.

Despite the widespread encroachment in Copper Canyon of deforestation, logging, mining, and an expanding drug trade that’s threatening to imperil their traditional way of life, these huarache-wearing endurance warriors have also shaken up the multi-billion dollar footwear industry. For the past several years, an increasing number of shoe companies have been manufacturing barefoot-style and minimalist running shoes for the masses. I read somewhere that it’s almost 10 percent of all running shoes sold. But there’s also a great deal of irony associated with this phenomenon: most of the 100,000 Tarahumara are totally unaware of their global impact on running today. Nor do they crave or want the attention or publicity. They run because that’s who they are. Their real name is Raramuri– an indigenous word that means “light feet,” as in fast running.

The late Micah True who was the Caballo Blanco figure in Born to Run was responsible for bringing attention to the Tarahumara. He had also organized an ultra run in Copper Canyon to raise awareness and buy food staples for the drought-stricken region. The event started small, but eventually attracted many local Tarahumara as well as several hundred runners from all over the world in 2012, just before True’s unexpected death from cardiac arrest during a 11-mile trail run in New Mexico.

My first “connection” with the Tarahumara occurred just before Born to Run came out, when I found myself in a six-day ultra in Costa Rica running alongside Scott Jurek who played a prominent role in the book. Two years earlier, in 2007, during the three-day, 250-mile, Pacific-to-Atlantic mountain biking race (La Ruta de Los Conquistadores) that I organize in Costa Rica each year, and listed by Time Magazine in the top ten of the toughest endurance challenges on the planet, I suffered a fall while riding the lead motorcycle. I broke my tibia and seriously injured my knee ligaments. It took me a year of hard work in the swimming pool to recover and doctors told me it was not a good idea to start running again. I set out to prove them wrong.

The very first running race I entered was the International Marathon of Costa Rica, a road race held every December in the capital city of San Jose. It took me 4 hours to complete the course, I felt sore but okay. Being able to run 26.2 miles gave me the motivation for a fresh challenge, so I signed up for a race called the Coastal Challenge, which was a six-day, 240-kiolometer off-road ultra through the jungles along the Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

My only real purpose in racing was to test my knee and other parts of my body that I had damaged in the past through past sporting accidents, including a very bad bike crash. I was pleasantly surprised on the first day of the race to find out that I was in fourth place. I really did not consider myself much of a runner but I guess I had a good day. In first place was Javier Montero, a well-known local racer who had won the race the year before, followed by Dave James ( USA 100-kilometer National Champion) and then the ultra-legend Scott Jurek, who was about 40 minutes ahead of me. I was especially happy to have finished without any pain in my mended body.

Back then, I had no clue as to who’s who in the ultra-community; for me the guys in front were just fast strong guys and I was mostly happy to be able to enjoy the scenery and do my best to test my late forty-something body. Day two of the race was the same: the top three guys broke away and finished in exactly same positions as on the first day. I was still in fourth.

Later that night at dinner, Scott, who was in third place, came up to me and said, “I came here to have a good time and this is my first event of the season. Can I run with you tomorrow?¨

I was honored by his invitation. I immediately said. ¨Yeah, sure. I am just doing this as a way to prove to myself that I can finish¨.

That is how I met and got to know Scott. For the next four days, we ran together in what turned out to be one of the most rewarding running vacations I have experienced. We ran up steep mountains, across rivers, through dense jungle and tropical savannas

Somewhere deep in the jungles of Costa Rica, Scott told me a story about having traveled to Mexico to run with the Tarahumara Indians. He said that they were very strong and fast and that their whole heritage was based on running, that they had games in which they drank this special drink made out of corn, and that then they would kick a wooden ball about for whole days and nights at a time. He said that when they were not running they would always sit in order to conserve energy by not standing around. Scott also mentioned that they were very poor, ran in sandal-like footwear called huaraches and liked music. He never mentioned that he had been in an actual race or that he had been beaten by one of them or the name “Caballo Blanco”.

We also talked about the vegan diet that he followed, which did not contain any animal products. He noticed that I was not eating enough and told me that after two hours it was essential to keep consuming easily digestible sugars. He shared some of his gels with me. After the race I was surprised to see everyone asking him for his autograph, even from the winner Javier.

My next exposure to the Tarahumara was during a promotional trip that I took to California to promote La Ruta mountain bike race that I have organized since the early 90s. On the trip a good friend gave me Born to Run to read on the flight back to Costa Rica. I was completely gripped and finished it on the plane. I knew the basic outline of the story, but not the whole thing, only bits and pieces that Scott had told me. At the time I had no idea I was going to be in close contact with these amazing people.

In 2012, my girlfriend Erika Hernandez was invited to run the La Sportiva UTMX, an ultra-marathon held in Hidalgo, Mexico. There she met the winner, a Tarahumara by the name of Aurelio Gonzales, a very small, shy and quiet Indian who had traveled with his coach and teacher, a professor named Jose “Chepe” Cervantes Camarillo. “Chepe” looks like a tribal chief; he is tall, big, dark and very well spoken. He acts as the mentor and representative of the greyhound-like Tarahumara runners. He explained to Erika that he had put together a group of about 300 runners whom he helps by taking them to races around Mexico and promoting their traditional culture. He hoped to get help from participants by asking for grain to be donated to the impoverished Tarahumara living in Copper Canyon. Because of Chepe´s charisma and Erika’s interest in history and indigenous culture, a deep friendship sprung up immediately.

When Erika came back to Costa Rica and told me about her experience, I thought it would be incredible to meet these people, learn from them and have the privilege to perhaps run with them. I decided to invite them to come to Costa Rica to run the first day of La Ruta mountain bike race. We had just wrapped up the twentieth year of the race, with 500 riders from all over the world. This is also the toughest day of the whole race, starting at the Pacific coast and going all the way to the small town of El Rodeo, a total of 100 kilometers. There are endless hills, stream crossings, unbearable heat, and mud along the well-marked route. Fifty percent of all riders usually fail to make the 12-hour cut-off time.

When I came up with the idea of La Ruta mountain bike race 20 years earlier, it was more of a biking expedition that only attracted few riders. About a dozen cyclists from the U.S. showed up in 1997, including multisport journalist Roy M.Wallack and Bill Katovsky, then editor of Triathlete magazine and current co-founder and editor of the Natural Running Center. Bill and I became quick, life-long friends. He was unable to complete the three legs of La Ruta, though he did make quite a sight on day two when he asked a support vehicle to carry his bike up the Irazu volcano while he ran up several miles of the long, uphill grade to the summit.

Bill recognized the potential of La Ruta, and his crystal-ball prediction came true years later as top team, pro and amateur riders from several dozen countries competed in what became known as the “toughest mountain bike race on the planet.”

Since La Ruta was an international mountain bike race, I thought it would be cool to celebrate its twenty years, not just with bikes, but with a running event! So Erika and I contacted our own Costa Rican indigenous tribes from up north, the Cabecares and Guaymies, to come and try the first ever 100-kilometer race called La Ruta Ultra. The idea was to make the race as destination for as many “natural runners” as possible. By natural runners, I meant people of all cultures, indigenous and non-indigenous, who love to run in a bio-diverse, natural setting like Costa Rica. Runners would compete in nature’s playground to celebrate peace, cultural tolerance and respect for the environment. It was my hope that one day the race would attract non-professional runners from countries such as Kenya, Ethiopia, South Africa, and even from the Hopi and Navajo tribes in the U.S.

The race could also become a newsworthy story that could spark interest in helping out the needy Tarahumaras. So with little time to spare, we talked to professor Chepe and sent him plane tickets for threee Tarahumara runners to come to Costa Rica for the race, talked to the Cabecares and the Guaymies, put ads on Facebook and in the local newspaper inviting all runners to take part in this incredible event. It was magical! We had a very positive response; both the main TV channel and principal local paper wanted to interview the Tarahumaras. But most of the local hard-core ultra runners were daunted by the prospect of 13,000 feet of climbing.

My First Meeting with the Tarahumaras

When Chepe arrived in San Jose, I immediately sensed a very positive soul with an incredible smile. He hugged me and said, ¨Well, here we are!¨

He had come with the winner of the La Sportiva UTMX, Aurelio Gonzales, 27, a small Indian who was quiet and shy and would not speak unless spoken to. His Spanish was not fluent, and Chepe often had to repeat his answers. Aurelio had also won the Guachochi Ultra Marathon and the Hidalgo 80km (both events in Mexico). The third Tarahumara was Silvino Cubesare Quimare, 34-years old and considered the fastest Tarahumara with the most international experience, having won many Ultra Marathons in Mexico, like the 100k Guachochi, the Urique 80km and several international Ultra Marathons, like the Bergmarathon, and the Otscher Ultra Marathon in Austria.

Somehow I recognized Silvino´s name from Born to Run, he was in it, he was part of the story, he was one of the runners who Scott had told me about. ¨Wow!¨ I thought, “I had the privilege of running with Scott Jurek and now I will be able to run with Silvino, the best of the Tarahumaras.”

The Tarahumara runners were dressed in their traditional dress—extra-long blouse-like top and thigh-length skirt—and many of the travelers at the international airport in San Jose stared at them and wondered what was going on. It was like traveling back in a time capsule to the ancient days of the Aztecs it was easy to imagine them running from the coast to the huge pyramids inland, carrying fresh fish to the kings (the Tarahumaras were the Aztec kings’ runners.

The Tarahumaras had brought a huge bag of handmade souvenirs to sell in order to take back some desperately needed money. They had also carried string instruments, a ukulele-like guitar and a violin (not only were they runners, but also artists and musicians.

I asked Chepe if they needed anything from the supermarket for the run and he told me that they would need tortillas and beans. The beans could be black or brown. Chepe told me that they do not drink or eat anything else during the race, except for a corn-based powder called pinole, which they mix with water and drink instead of energy drinks or gels.

We stopped at the local store, bought the beans and tortillas and took them to the bed and breakfast where they could rest from their long trip. The Tarahumaras had had to walk for eight hours to get to Chihuahua before the two-hour flight to Mexico City and then another four hours on the plane to Costa Rica.

The Local Runners

One of the first runners to take up the La Ruta Ultra challenge was Kurt Lindermuller, a German who has been living in Costa Rica for over 20 years. Kurt is probably one of the best ultra runners in Costa Rica and placed eighth at the Badwater Ultra marathon in Death Valley in 2012, as well as winning the Brazil Ultra marathon in 2011. Kurt is tall, pale and strong, with the engine of a well-tuned Mercedes Benz and the killer drive of a Rottweiler on a hunting spree. If he senses weakness in a competitor he will push the pace until the other runner’s breaking point. Not many can keep up with his relentless pace. ”Now we have a real challenger for the Tarahumaras,” I thought to myself.

The second local runner to step up to the challenge was Ligia Madrigal. She is considered the best female adventure racer in the country. She has done many ultras including a 100 mile event as well as many international adventure races. She is unstoppable. Another of the local veteran racers who decided to accept the challenge was Daniel Seravalli. He has completed the Marathon de Sables, a six-day, self-supported race held in Morocco, and considered one of the toughest endurance challenges.

As I previously mentioned, we invited a small group of indigenous runners from the Cabecar tribe, who live in the Talamanca mountains in the north of Costa Rica. To reach the start of the race they had to walk for six hours, then take a bus for three hours and a second bus for two more. The Cabecares were a family consisting of 4 members. The oldest was Luis, who came with his two sons Roy, 18, and Cesar, 15, and his 13-year old daughter. They had the same demeanor as the Tarahumaras, shy and soft spoken, except for Roy, who was a typical extroverted teenager with a rebellious, no- fear attitude and hair shaved into a Mohawk. They had all participated in the toughest trail run in Costa Rica, the Chirripo Race, a 34-kilometer up and back to the summit of our highest mountain.

The field for the inaugural La Ruta was small, but we were a spirited bunch. The night before the race, all 21 of the first-time La Ruta runners had a chance to meet and have dinner together in the coastal town of Jaco. The Tarahumara sat together in one corner the Cabecares in another and the rest of us in the middle of the table. It was a really pleasant encounter of cultures in what would become a brotherhood forged by sharing the same tribulations and physical pain that we were to experience the next day. I too was going to run.

The Race Begins

At 6 am with the temperature in the high 70’s, we set out from beneath the billowing Red Bull inflatable. The group soon split up: the frontrunners were Aurelio and Silvino, Luis, Roy and Cesar, Kurt and me. For the first 45 minutes we ran at a fast pace and as soon as we hit the first climbs, Luis, Roy and Cesar picked up the pace followed closely by Silvino, Aurelio and Kurt. I was unable to keep up and decided to run my own race. I was the only runner who knew the course,having done it numerous times on my mountain bike over the past 20 years. I knew it was going to be a long hard day and was surprised at the fast pace by the leaders.

As we got close to the midway point, I started picking off the Cabecares one by one. They had gone too fast too soon and were wearing brand new running shoes that had been given to them the day before the race. At the North Face aid station all the Cabecares had to quit, partly due to blisters on their feet and partly because they had never run more than 35 kilometer in a competition before.

Meanwhile, both Tarahumaras and Kurt had passed through this aid station about 30 minutes earlier.

I was feeling okay and kept up my steady pace. The next aid station was 17 kilometers away, all uphill with about a 20% gradient. When I finally got there the Tarahumara had an hour on me, but Kurt was only 3 minutes away. I knew he was hurting and that catching him up was only going to be a matter of time, as long as I did not blow up myself. In these kinds of events, it’s never over until you have crossed the finish line. As I was leaving the aid station I saw Daniel (the Marathon de Sables finisher) ahead of me. He had not overtaken me on the course but had missed a sign and taken a route which was about 1.5 hours shorter and with a gentler ascent. By this time we had gone 70 kilometers. I could see the Central Valley now and the sun was setting. I was only 30 kilometers from the finish. Somehow I still had some energy left and I knew every step of the way.

I reached the finish line three hours later at about 8:30 pm. Kurt, my German buddy, had to quit with only three kilometers left. He had taken in too many salts and his body was shutting down. Ligia came in about an hour after me; she looked very fresh, as if she had only run a 10K.

Out of the 21 adventure runners, six of us ran from Jaco, the coastal town, to the finish line at El Rodeo, but only four covered the total distance. Silvino won the race in 11 hours and 52 minutes; Aurelio came in a minute later, both of them had been trading positions all day long and in the end Silvino had the upper hand. Daniel and Andres Vega missed signs and ended up crossing the finish line as well. They had a very tough day out there and even though they did not do the same course as the rest, I knew they had made their own personal journeys and paid their dues to the pain gods.

As for the two Tarahumara runners, Silvino and Aurelio, I didn’t detect that they were ever in any pain or discomfort during the race, though I was only able to run with them for about 45 minutes, then I was unable to keep up with their pace. What I noticed was the following: they would take shorter steps than what I was used to but at a quicker cadence. Their bodies were either straight or with a slight lean forward; their feet followed. They did not use their arms very much, with hardly any swinging and close to their bodies. Their running form was almost identical. They were silent when they ran in their huaraches; you could hardly hear the footsteps compared to mine At the aid stations they would only take pinole (a corn-based drink) and tortillas with beans; they avoided the Coke, Powerade and gels. They did not stop for long at the stations, and then they were gone like ghosts.

The next day I woke up at 5am, left Erika at her workplace and went back to bed. I had to take our Tarahumara friends back to the airport. On our way there I finally heard a few words from Silvino. He told me that was the hardest 100 kilometers he had ever done and that they were used to finishing a race this long in eight hours, not twelve. I smiled and said, ¨Yeah it really knocked me out.¨ When we reached the airport Chepe, Silvino, Aurelio and I hugged and they invited me to come to Mexico to run in their country and told me they would come back next year for the second La Ruta Ultra. I felt very proud to have earned their respect and friendship.

Running with the Tarahumara in Mexico

In the weeks following the race, Channel 9, a local television station that covered the event, put together an excellent 30-minute documentary. News of the winners got back to Mexico and a few months later Professor Chepe called me and told me that the main newspaper in Aguas Calientes, Mexico, had offered to organize a 100-kilometer race, all the proceeds of which would go to the Tarahumara. They had asked that, besides the payment of the entry fee, runners registering should also donate grain and non-perishable food.

Chepe asked me to come to this first edition of the Heraldo 100K as a special guest. I told him I would be there. I started organizing our trip to Mexico. There would be three of us heading north. My sister Florencia would be in charge of PR and the cultural side of the trip. More than just an ultra marathon, this was to be a cultural experience; we would try to learn from the Tarahumara and from the race organizers. Florencia would be in charge of taking photos and handing out flyers for the second edition of our race. This suited her very well as she had been the director of the national museum of art here in Costa Rica and an artist all her life. She is extroverted and talkative and easily wins the hearts of whomever she comes into contact with. Erika was the original connection with the Tarahumara; she was thrilled to be going back to Mexico to run and represent La Ruta over there.

A few days before we departed, I received a call from Christian Lesko, a friend of mine, who told me he was training for the Adventure Racing World Championships that were going to be held at the end of the year in Costa Rica. I said, “Wow! This would be a great way to test your mind and body.“ He agreed and joined the group. Now there were four of us going to Mexico to run with the Tarahumara.

After a long flight we finally arrived in Aguas Calientes and were greeted by a smiling physical education teacher by the name of Gustavo, who would be our host for the remainder of our trip. Gustavo drove us to an athletics center with a good sports facilities, including a 25-meter covered pool, a velodrome and dormitories for guest athletes. As we entered the guest facilities, we found a group of about 20 Tarahumara Indians wearing their traditional dress waiting for us. They danced and played instruments and had gifts for us, including dresses for Erika and Florencia and headdresses for Christian and me. It was an incredible feeling to be greeted in such a welcoming manner. They offered us food and drinks, but I did not accept their offer since we were going to be racing in two days and I did not want to risk eating stuff that my body was not used to.

The next day we were invited to a get-together with the Tarahumara at a small farm just outside the capital city of Aguas Calientes. The Tarahumara played violin and guitars and sang in their language for hours, they danced and played with their traditional wooden ball, which they kicked and chased. Out of the twenty people in the Indian group, eight were runners. The oldest was about 50 years old but looked much older, maybe because of the hard life I imagined he lived. Then there were three runners who looked as if they were in the 30s and four more who looked much younger, in their 20s. Among them were Silvino, who had won La Ruta, and a young woman called Luz Elva, who was to represent the Tarahumara women and run 21 kilometers of the 100-kilometer race. The non-runners were musicians and dancers and there was even a baby girl, a year and 8 months old, whose name was Zoe Golondrina. She was the daughter of Martin Makawi, the spiritual leader, a chief-like character whom all the Indians respected and looked up to. He was the only one besides professor Chepe who addressed the non-indigenous people directly.

Zoe was looked after not only by her parents Martin and Clorinda, but the rest of the group. She felt safe with each of the members of the tribe. She had fewer restrictions than I have ever seen with any other toddler in North or South America.

As the sun was setting we headed to a small town 21 kilometers from Aguas Calientes where our indigenous friends were putting on a dance show and also setting up a few tables displaying their artwork to sell to the audience. We spent several hours watching their interesting dancing and songs and then went back to the athletics facilities in Aguas Calientes. I was very hungry because I had not eaten any of their food, except some rice that did not have any chili in it (in Mexico hot spicy food is the rule). My stomach is not too tolerant of these types of dishes. The next day we were again invited, this time to a presentation at the Aguas Calientes Golf Club where the rich locals hang out. It was odd watching the rich ladies looking disapprovingly at the indigenous people and giving them dirty looks. They had these “what are these people doing here?“ types of expression. As if often in the case in Mexico and South America the indigenous people are not considered to be equals and are perceived as dirty and lazy. They get very little respect.

Nonetheless, the golf club secretary received us with open arms and had a special pre-race meal prepared for us consisting of pork, rice and beans, potatoes and salad. The Tarahumaras were impressed and very happy. Once again I had only potatoes and salad.

Race day: We had been told by our host Gustavo that the race organization was going to be superb, with food and water stops every 2 kilometers, and that 70 percent of the course would be on gravel or trail. Great. I thought, I wouldn’t have to wear a Camelbak.

Before dawn the Tarahumaras cooked a huge breakfast: eggs, ham, rice, beans and a whole lot of other grainy and saucy looking foods with a lot of spices. The smell was fantastic but I once again decided against new foods and had my usual chocolate milk, yogurt , bread and orange juice. It was a cool morning and all the 450 participants gathered in front of the offices of the Heraldo, the main newspaper in Aguas Calientes. The Tarahumara did their traditional dances blessing the event and calling on the spirits to keep all the competitors safe. The smell of incense filled the cold morning air.

When the starting gun went off I knew it was going to be a long hard hot day, but had little clue as to what to expect. This is what I find attractive about doing ultra-running races: the adventure of dealing with the unexpected. Every race poses its own particular challenge and you learn a lot from each event. I had never run on such a flat course such as this one in Aguas Calientes; 100 kilometers with only 300 meters of elevation gain in total over desert-like terrain. The Tarahumara are not accustomed to running on flat courses like this either; they live in the Copper Canyon where the mountains are steep.

I realized the information we had been given about the aid stations was simply not true. We had aid stations for the first 21 kilometers but then it all collapsed – there were no stations at all. Nine kilometers later, I saw a support vehicle, stopped it and got cold water and food. I had taken a few packs of gummy bears and I told the support truck that I was okay and if it was possible for them to wait for me at 40km.They agreed.

I slowed the pace but kept going. An hour passed, then two, with no water and nowhere to hide from the sun. I knew I had passed 40 kilometers by then and changed from being a competitor to merely trying to survive. Finally I saw the support truck. A volunteer told me they had had to help the rest of the racers in front since there was no water. Four of the nine Tarahumara runners who had started had dropped out; one was in hospital with severe dehydration. Oh, I forgot to mention that the course was not 70 percent gravel; it was 98 percent pavement. The Tarahumara are not used to running on asphalt and some of then were in pain because their huaraches were melting and their feet were burning. Natural runners are not meant to run on pavement!

I slowed the pace but kept going. An hour passed, then two, with no water and nowhere to hide from the sun. I knew I had passed 40 kilometers by then and changed from being a competitor to merely trying to survive. Finally I saw the support truck. A volunteer told me they had had to help the rest of the racers in front since there was no water. Four of the nine Tarahumara runners who had started had dropped out; one was in hospital with severe dehydration. Oh, I forgot to mention that the course was not 70 percent gravel; it was 98 percent pavement. The Tarahumara are not used to running on asphalt and some of then were in pain because their huaraches were melting and their feet were burning. Natural runners are not meant to run on pavement!

Sometimes in sports there are times when it is best to wait for another day and try again, at least for me. I see life as the race and I see no honor in reaching the finish and passing out or crawling across the finishing line. In Costa Rica, we have a saying: “it’s not about being the first to finish, it’s about how you get there”. Feeling very dehydrated and tired, I decided to call it the day and stop at 68 kilometers where there was a rest station. As I sat there I watched other brave runners pass by, the team from Japan, a few Mexicans (no Tarahumara, they were all in the front pack – well, at least the ones that remained in the competition).

As I sat there thinking of how good the shower and bed were going to feel, I heard a radio message from the sweep vehicle that had been accompanying the very last runner. It was my teammate from Costa Rica, Christian, the message did not sound good according to the report. So I got into the support truck with cold water and some food and drove back until we found him at the 55-kilometer mark. I asked him how he was feeling and he told me he really wanted to finish his first 100-kilometer run. I put on my cap, smeared on some sunscreen and told Cristian we were both going to finish the damn race. Now I had a mission, I was going to use all my knowledge and experience to try to get us through in good shape.

We hiked and ran the rest of the way. I would motivate him and tell him what to eat and remind him to drink. At 80 kilometers we were not last any more; we had caught up with two Mexican runners (not Tarahumara), one of whom was the 100K national champion. He was also hurting very badly so I helped him and pushed him. It was the threeamigos for a while, almost 2 hours. Then Christian had to stop to pee and we never saw the Mexican again until we reached the finish line. The other Mexican runner we had passed quit at 85 kilometers, so we were once again dead last.

It took us 15 hours to reach Aguas Calientes.

Usually when you are last there is no glory, there are no spectators. There is no one waiting unless it’s your family or friends. Running with the Tarahumaras in Aguas Calientes was different. As we ran the last few meters, we were greeted by tearful Erika who had quit at 40 kilometers due to dehydration. As we reached the last 100 meters a few of the Tarahumara, including Martin and Clorinda, ran together with us. A young Tarahumara had won the race in 8 hours and 10 minutes, but instead of going back to the athletic facilities for showering, eating and resting, he waited with the other Tarahumara runners and spectators until the Ticos (what they call us Costa Ricans) made it in. Though we were the last to finish but had earned their friendship and respect. We were all crying and hugging each other in a way only a person that has finished an Ultra knows. A few minutes later they did their traditional closing of ceremony dance.

To end a perfect day Florencia had booked a great hotel right at the finish line so we did not have to go to the athletic village and share bunk beds with the rest of the athletes. I felt kind of bad in a way; they had waited for us for 7 hours and now we decided to go to a hotel instead of sharing with them at the village. I was so tired that I just wanted to get some rest. Although it was probably a politically incorrect decision, in hindsight it was the best thing we could have done. You see, the Tarahumaras — as their tradition goes – decided to celebrate by drinking a special drink called tisguino that is made out of fermented corn, and got drunk and danced, chanted and sang until dawn. I was so dead-tired after reaching the finish line that this would have been too much.

On the way back to Costa Rica, I was sad that it was all over. This post-event emotional letdown happens every time you move beyond your comfort zone for any period of extended time. But on the positive side, I was motivated by my athletic and cultural immersion with the Tarahumara, and want to help these amazing natural runners as best I can. I hope to attract runners from around the world for the second annual La Ruta Ultra Run in November, and so that they too can experience the magic of running with the Tarahumara. Many of the Tarahumara runners whom I met in Mexico said through Professor Chepe that they will be there. They should like the race course in Costa Rica: it’s mostly off-road and it’s not flat either, with almost three miles of total elevation gain.

For more info and race registration details about La Ruta Ultra Run that will be held on November 16, 2013, go here.

My favorite runs in Seattle: Green Lake: I run around Green Lake a lot, mostly because it’s convenient and if I need to just clock some miles I can run a couple loops. Discovery Park: I live in Fremont and I know a loop that runs from my house, through the Ballard locks, around Discovery, and home. It’s a 12 mile loop and you get a little bit of everything: city roads, trails, jungle, swamp, beach, and steep hills. I run here a few times a week, typically in the afternoons. If you see a hungry-looking dude doing repeats on the south steps it’s probably me. Cougar Mountain: I run here when I need some serious hill training. Also, I run here when I need some serious cougar/bear combat training. My favorite runs in the world: Mt. Fuji: I sort of ran up Fuji. I ran in the middle of the night to catch the sunrise and it’s quite steep and dark up there, so mostly it was like a really fast hike. Monteverde Cloud Forest, Costa Rica: My brother, girlfriend and I snuck into the Monteverde Cloud Forest after dark and ran through the jungle. There were lightning bugs on the ground below and shooting stars in the skies above, and we eventually got chased out of the park by rangers on motorcycles. This experience qualifies as one of the best runs of my life. Nagoya, Japan: This is where my crazy bamboo-lightning run happened. I don’t know the name of the forest I ran in but it was in the Meitoku neighborhood of Nagoya. Also, that purple drink is still in those vending machines as far as I know.

So excited for La Ruta!

I am currently co-producing a documentary featuring the Tarahumara , the most indigenous tribe in North America. The Tarahumara are renowned for their long distance running ability and remarkable resistance to the top 3 modern diseases – cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. Our documentary, Goshen, links their extraordinary health to their indigenous diet and extremely active lifestyle.

In March 2013, we got to live among one of the remote Tarahumara communities for a month and document the ir way of life in the remote depths of the Copper Canyons, Mexico. We believe your readers will be inspired by the Tarahumara lifestyle.

If you are interested, we would appreciate any promotion for our documentary film. You can find more details about the film at http://www.goshenfilm.com

Thank you for your time and consideration,

Sarah Zentz & Dana Richardson

Dana & Sarah Films LLC

thanks Dana. would love to know about their resistance to the modern diseases. we are teaching this stuff to medical students. Mark

great, full La Ruta 2013 race report here, with photos:

http://www.irunfar.com/2013/11/2013-la-ruta-run.html

La Ruta Run was awesome: http://rundavejames.wordpress.com/2013/11/27/pura-vida-la-ruta

Wow! Such an infusion of joy! It’s hard to believe you’re writing about such grueling experiences. Thank you!

This is such a great story, well told. I came here looking for more about the Tarahumara. Love the humility with which you laid out your journey. I’m getting into running, and while I like it for the athletic side, the part that keeps me most interested is the community, and it looks like you have it in abundance. I’m looking forward to more of it!