Ed Ayres, who has been running competitively for 55 consecutive years, was the founding editor and publisher of Running Times magazine. Ayres has competed in over 600 long-distance races, including finishing third in the inaugural New York City Marathon. He’s also the author of the new book, “The Longest Race: A Lifelong Runner, an Iconic Ultramarathon, and the Case for Human Endurance,” which is a reflective, personal memoir of running the 2001 JFK 50 Mile, while narrated against the backdrop of lessons learned as a lifelong competitive runner and journalist. In the following excerpt from The Longest Race, Ayres describes the circumstances surrounding a much-discussed 1979 issue of Running Times when it published the results of a study of 120 models of running shoes. Controversy, of course, ensued.– NRC

***

In the October 1979 issue of our then two-year-old magazine, Running Times, we published the results of a study of 120 models of running shoes that had been conducted for us by a prominent sports podiatrist, Joseph Ellis. As we noted in the accompanying article, “Previous studies have always emphasized laboratory analysis of the materials and design of the shoe. The Running Times study emphasizes analysis of the feet and legs wearing the shoe, rather than the shoe itself. This, ultimately, is what the evaluation of a shoe is for: to determine how well the shoe supports the natural motions of the legs and feet—and how well it protects them from injury—during the running motion.”

In the October 1979 issue of our then two-year-old magazine, Running Times, we published the results of a study of 120 models of running shoes that had been conducted for us by a prominent sports podiatrist, Joseph Ellis. As we noted in the accompanying article, “Previous studies have always emphasized laboratory analysis of the materials and design of the shoe. The Running Times study emphasizes analysis of the feet and legs wearing the shoe, rather than the shoe itself. This, ultimately, is what the evaluation of a shoe is for: to determine how well the shoe supports the natural motions of the legs and feet—and how well it protects them from injury—during the running motion.”

We used ten test runners for the study—five males and five females. The male runners ranged in ability from a ten-minute-per-mile beginner to a world-class competitor (Craig Virgin, who had broken Steve Prefontaine’s American record for the 10K just the previous year). The females ranged from a twelve-minute-per-mile beginner to a world-class competitor (Laurie Binder, a national marathon champion and four-time winner of the San Francisco Bay to Breakers race). The runners were wired to test shock (G-force transmitted up the leg to just below the knee) and motion control (behavior of the foot at forty-two equal-time points in the cycle of each step taken). A total of six hundred test runs were recorded.

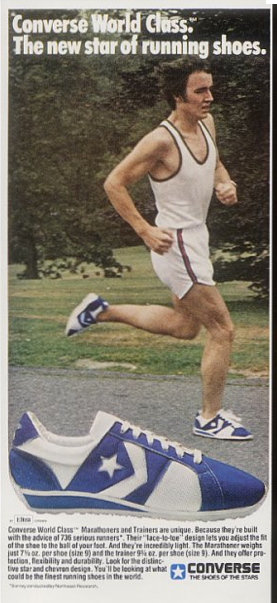

The study caused a huge ruckus. It had covered the full range of models being marketed to runners and joggers that year, including models that sold for very low prices in mass-market chain stores—knockoffs that looked similar to the shoes serious runners wore, but that if you tried running in them turned out to be bricks. In identifying the results for specific models, however, we just listed the models that tested “very high,” “high,” or “medium” in the tested qualities. But a number of readers complained that we had not named all of the 120 models tested, including the ones that had performed poorly, so in the following issue we went ahead and named them all. And that was when that metabolic by-product we’d been taught in grade school to call “number two” hit the fan.

The study caused a huge ruckus. It had covered the full range of models being marketed to runners and joggers that year, including models that sold for very low prices in mass-market chain stores—knockoffs that looked similar to the shoes serious runners wore, but that if you tried running in them turned out to be bricks. In identifying the results for specific models, however, we just listed the models that tested “very high,” “high,” or “medium” in the tested qualities. But a number of readers complained that we had not named all of the 120 models tested, including the ones that had performed poorly, so in the following issue we went ahead and named them all. And that was when that metabolic by-product we’d been taught in grade school to call “number two” hit the fan.

In the full listings, the very bottom shoe—117th of 120 in shock protection and dead last in motion control—was a model called the “USA Olympics.” The name caught our attention because that model was one of the cheap knockoffs that we were pretty sure no Olympic runner would ever wear. Yet, we also knew it was against the law for any commercial product to use the Olympic name without permission of the US Olympic Committee. So, this use (by a giant mass-market chain store) had to be an endorsement! The USA Olympics shoe had a shock reading of more than ten Gs transmitted up the leg—about five times as much as the shoes ranked at the top. We wondered: Would thousands of beginners be injured because they’d been misled by what looked very much like an Olympic Committee endorsement for a shoe that was actually a brick?

Our concern was further elevated when, after our story made the front page of USA Today, the chain’s national management called a press conference to “refute” our results. To testify to reporters that the USA Olympics was “as good as any shoe on the market,” the company had brought a biomechanics expert—a guy we’d never heard of. We did a little investigating of him and, after wading through a byzantine web of corporate connections, found that this “expert” was the same man who had designed that model in the first place and was now on the payroll of the chain that was selling it! It was a scandal, and being the eager young journalists (and hard-core runners) that we were, we decided to do an exposé. We were immediately informed that if we did, we’d be sued. We went ahead anyway, with a cover story in the January 1980 issue, “The Great Olympic Shoe Scandal.” I coauthored the article with my associate publisher, Jeff Darman, who had been president of the Road Runners Club of America for the previous three years. No one sued. And ever since then, there’d been a general understanding among serious runners: Buy your shoes at a “running store,” from a salesperson who is himself or herself an experienced runner. Don’t buy cheap knockoffs at a department store, or your feet and knees will regret it.

Our concern was further elevated when, after our story made the front page of USA Today, the chain’s national management called a press conference to “refute” our results. To testify to reporters that the USA Olympics was “as good as any shoe on the market,” the company had brought a biomechanics expert—a guy we’d never heard of. We did a little investigating of him and, after wading through a byzantine web of corporate connections, found that this “expert” was the same man who had designed that model in the first place and was now on the payroll of the chain that was selling it! It was a scandal, and being the eager young journalists (and hard-core runners) that we were, we decided to do an exposé. We were immediately informed that if we did, we’d be sued. We went ahead anyway, with a cover story in the January 1980 issue, “The Great Olympic Shoe Scandal.” I coauthored the article with my associate publisher, Jeff Darman, who had been president of the Road Runners Club of America for the previous three years. No one sued. And ever since then, there’d been a general understanding among serious runners: Buy your shoes at a “running store,” from a salesperson who is himself or herself an experienced runner. Don’t buy cheap knockoffs at a department store, or your feet and knees will regret it.

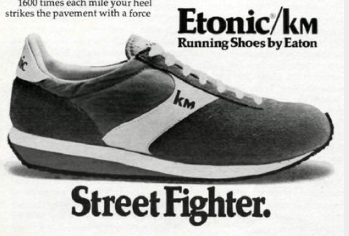

Of course, that was not the last chapter in the saga of a runner and his shoes. As the number of people participating in road races boomed, the market for good shoes became ever more competitive, and—as had happened with cars—the release of new models of shoes goosed sales and launched a sort of running-shoe arms race. The cheap models were left in the dust, but the serious brands—Adidas, Nike, New Balance, Reebok, Saucony, Lydiard, Etonic, Mizuno, Brooks—sought ways of gaining an edge, and one way was to make the shoes lighter. Elite runners—those rare individuals who had perfect form (no excessive pronation or body weight, etc.) felt they could run faster if they could cut an ounce or two from the weight of their shoes. Manufacturers were happy to accommodate, and “racing” shoes—dropping amidst great fanfare from thirteen ounces to twelve, to ten, to eight, to something called the Nike Sock Racer, which weighed almost nothing at all—became a booming business. I tried a few of them (though not the Sock Racer) and nearly collapsed my arches. By the time I was forty, I knew I’d have to run my races in the same kind of supportive shoes I trained in, probably for the rest of my life. The thirteen-ounce Saucony shoes I was running in for the JFK were the same ones I’d worn in my training runs for the past month.

Of course, that was not the last chapter in the saga of a runner and his shoes. As the number of people participating in road races boomed, the market for good shoes became ever more competitive, and—as had happened with cars—the release of new models of shoes goosed sales and launched a sort of running-shoe arms race. The cheap models were left in the dust, but the serious brands—Adidas, Nike, New Balance, Reebok, Saucony, Lydiard, Etonic, Mizuno, Brooks—sought ways of gaining an edge, and one way was to make the shoes lighter. Elite runners—those rare individuals who had perfect form (no excessive pronation or body weight, etc.) felt they could run faster if they could cut an ounce or two from the weight of their shoes. Manufacturers were happy to accommodate, and “racing” shoes—dropping amidst great fanfare from thirteen ounces to twelve, to ten, to eight, to something called the Nike Sock Racer, which weighed almost nothing at all—became a booming business. I tried a few of them (though not the Sock Racer) and nearly collapsed my arches. By the time I was forty, I knew I’d have to run my races in the same kind of supportive shoes I trained in, probably for the rest of my life. The thirteen-ounce Saucony shoes I was running in for the JFK were the same ones I’d worn in my training runs for the past month.

On the other hand, my diligence with the Sheehan mantra led me to a kind of epiphany about what “listen to your body” really meant. We humans (and maybe other species as well) don’t just sense what’s happening in our bodies through the mediation of our consciousness up top in the ivory towers of our heads, but also directly through our hearts, groins, skin—and feet. I rationally accepted my need for sturdy shoes, but at a deeper level, I felt a kinship with our ancient predecessors —and maybe it was a yearning not just for more connection with my heredity as a human, but for more direct and intimate connection with the earth on which we had evolved. I didn’t believe for a minute that runners were drawn to lightweight shoes only so they could run faster 10Ks or marathons. A big part of it, I suspected, was the genetic memory of how it feels to run barefoot

On the other hand, my diligence with the Sheehan mantra led me to a kind of epiphany about what “listen to your body” really meant. We humans (and maybe other species as well) don’t just sense what’s happening in our bodies through the mediation of our consciousness up top in the ivory towers of our heads, but also directly through our hearts, groins, skin—and feet. I rationally accepted my need for sturdy shoes, but at a deeper level, I felt a kinship with our ancient predecessors —and maybe it was a yearning not just for more connection with my heredity as a human, but for more direct and intimate connection with the earth on which we had evolved. I didn’t believe for a minute that runners were drawn to lightweight shoes only so they could run faster 10Ks or marathons. A big part of it, I suspected, was the genetic memory of how it feels to run barefoot

***

Excerpt from “The Longest Race: A Lifelong Runner, an Iconic Ultramarathon, and the Case for Human Endurance, copyright Ed Ayres, 2012. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, The Experiment. Available wherever books are sold.

Ed,

thanks for this great story and for all the knowledge you share in your book. it is a must read for all NRC members. Ed masterfully chronicles his adventure in the JFK 50 Miler (a race i have completed 3 times) and weaves in just about everything one needs to know about running and racing an ultra.

the best shoe testing now is done by Jay Dicharry. yes he measures the runner and how the shoe affects the joints.

agree be catious taking advice of someone who is on the payroll of the company supporting the “research”. not that all is wrong….just do your own homework and have a catious skepticism if the results weigh strongly in favor of their products. This goes for pharmaceutical research as well.

Mark

Just out of curiosity, is there anywhere I can read the results of the 1979 test?

Thanks,

Joey