In 1994, seven CEOs from the nation’s largest tobacco companies declared under oath before a Congressional hearing on Capitol Hill that “nicotine is not addictive.” Their testimony was a brazenly defiant refusal to acknowledge the legitimacy of several decades of research that proved cigarettes and nicotine were health hazards. Now imagine that in a parallel universe it had been seven CEOs from the nation’s largest footwear companies all making the following declaration before that same Congressional Subcommittee on Health and the Environment: “Over-supported running shoes do not cause foot or leg injuries.” Even though a number of published footwear studies already indicated that this was the actual case, the running shoe CEOs were in lock step agreement that it was not.

But there’s more. Since their well-padded shoes were marketed as a way to prevent injuries, did these companies need to apply for FDA approval as stipulated by federal regulations for most other consumer products? No, the shoe companies didn’t need a green light from the FDA. The shoes companies did no safety studies on runners, submitted no papers to scientific journals, or got their “devices” approved for public use.

So why hasn’t the FDA required footwear companies, like most other consumer health-related products, which range from manual toothbrushes and wooden tongue depressors to blood pressure devices and even hot and cold packs, to be first tested to ensure that they not only are safe, but they do what they claim. In the case of the typical modern thick-soled oversupported running shoes, footwear companies have been given a free pass.

Here’s the catch. Somewhere along the way, shoes and shoe products of all types, including those worn by surgeons and nurses in a hospital’s operating room, inserts given to patients by therapists for treatment, therapeutic shoes, running shoes, and even “toning” shoes,” which claim both health and fitness benefits, are exempt from premarket testing. They are exempt by the FDA much like potentially harmful dietary and vitamin supplements can be sold to consumers without first being rigorously tested by a government agency.

Early last month, discussions on injury, minimalist, barefoot running, and conventional footwear on Zero Drop, which overflowed to Runblogger, with input from yours truly and many others, including Simon Bartold, head of research at Asics, addressed what for so long has been the elephant in the room. A call finally came for real research to study running shoes and injury. While it’s superb idea, I doubt that it will ever happen, at least in the way that the study should be conducted.

The proposed study was that each shoe should be rigorously tested using runners to find out once and for all whether the big-bonker shoes cause injury, if minimalist shoes fare better, and whether barefoot is best and perhaps the gold standard for healthy running.

But performing studies that clearly show whether a specific running shoe is good or bad is not going to occur. The million-plus dollar price tag alone would forbid it. And to do it correctly would take many years of testing; but shoes come and go in the market rather quickly. The cost, of course, would be passed on the consumers in the form of higher shoe prices.

But why should consumers pay for studies to help for-profit (and big profits they are—in the billions of dollars) companies demonstrate their shoes are harmful or not?

Many good studies on shoes and the potential for running injuries have been performed and published in respected medical and footwear science journals; and there are no doubt more of these studies underway right now. Moreover, the barefoot and minimalist movements, have done one additional thing: increased the interest of researchers and made more funding available.

Another reason the ideal running shoe/injury study can’t be done is because they have to use humans who have many variables. These include gait irregularly, postural distortion, muscle imbalance, and physical pain. This practically guarantees that it will be a short-term study. Since a published study usually lists its own limitations—scientists and journals require this as a way to appear more objective—these criteria are just babbled back by skeptics, in this case the public relations folks at shoe companies right back to the media.)

The types of studies typically performed by researchers also won’t satisfy most runners. Human studies typically demonstrate some “average” outcome, but consumers want to know “what does this mean for me.” For these studies, the conclusions can’t be narrowed to any one individual.

But the truth remains that many published studies already demonstrate the damage caused by conventional running shoes, or even walking in bad shoes. One of the earliest published studies describing the harm from shoes came in the early 1950s when a Canadian scientist, Dr. John Basmajian, showed that wearing shoes affected foot function through impairment of muscle activity. Known for his work in the area of electromyography (EMG) and biofeedback, the work of Basmajian and colleagues played a key role in other studies, later demonstrated by another Canadian, Dr. Steven Robbins, followed by Dr. Casey Kerrigan and her colleagues. The list goes on.

Instead of the endless call for “more studies are needed,” there’s a better idea—a system of checks and balances already in place. It’s to lobby Congress to insist that the FDA follow its own guidelines and require running shoes to be pre-market tested on human subjects—and not by machines as many running shoe companies currently do in their research and development labs– to demonstrate health and product safety. But getting the FDA to change its stance probably won’t happen as the big shoe companies command so much money and lobbying power on Wall Street and Capital Hill. And money talks.

Just as important as the published studies is real-life clinical evidence. There are many healthcare practitioners—from podiatrists and medical doctors to chiropractors and physical therapists—who have long been in the trenches treating injured runners before the shoe companies changed their products from flat minimalist shoes to oversupported ones (which began to occur around 1980). We saw how significant a runner’s body responded to the increasing thickness of shoes, including which muscles were most damaged by oversupported racers and trainers. This is the ultimate scientific inquiry—years of flat shoes, then years of thick shoes, now years of modern minimalist shoes. The combination of clinical observations with scientific evidence is a meaningful application of evidence-based medicine.

Clinicians who understand biomechanics could see the changes in the running gait as flat shoes became thicker and more cushiony. I treated thousands of runners, and often had them bring me their different shoes to evaluate how their body functioned in each pair. Finding the best pair usually meant flatter, less support. In addition, the immediate and dramatic change in virtually any runner who takes off his or her shoes and runs for just a few steps is obvious, at least for those who are open minded and interested in a runner’s health.

Perhaps an even better approach is to employ one, two or all three critical factors that already exist. First, for those who want more scientific explanations, they should look at the extensive peer-reviewed research studies published since the 1950s that demonstrate how shoes are harmful. Second just watch a person running in these oversupported shoes, and compare their gait when running with very flat shoes. Third, just take off your own shoes and run. If you don’t feel the force of being barefoot, perhaps you’re taken in by the marketing propaganda. But it’s never too late to break with the past. In other words, kick the habit.

I couldn’t agree more! While shoe companies may argue that long-term clinical studies to look at say, knee osteoarthritis, may be impossible, we have a number of variables that actually can and should be evaluated now. About every large athletic shoe company (and university) has a gait laboratory with force plates and motion cameras. What I would like to see is for these labs to be used to measure and report meaningful data (as opposed to the meaningless but snazzy looking data often used for marketing). Peak knee joint torques (forces applied a distance from the knee), has been linked to the development and progression of knee osteoarthritis. These can be measured in a gait laboratory. Claims of “cushioning” gotten from machine testing have absolutely no meaning in relationship to when in the gait cycle these peak joint torques (and other peak forces related to injury) occur. How a shoe sole actually works under a foot, again, all can be easily tested – now.

As an exercise physiologist / biomechanist by training, researcher by profession, and fully barefoot runner by hobby, I echo Dr. Kerrigan’s comments regarding the ability to perform meaningful research now in virtually any gait lab, whether it resides in industry or an academic setting. Mechanical testing of the physical characteristics of various footwear technologies is, in my humble opinion, of so little value as to be virtually pointless as it regards knee biomechanics during running and the development of such musculoskeletal disorders as osteoarthritis. The good news is much important work is underway or being planned right now, so with good fortune we should gain valuable insights in the not too distant future.

Phil,

thanks for the contribution.

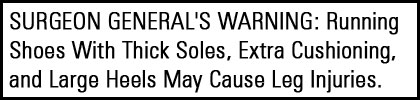

An important piece and maybe the parody warning will one day be real.

A similar problem has occured in football helmets and we are just now realizing the harm. When companies started creating football helmets with no regulation on how the head was affected in the collisions, all assumed they must be a good thing. Of course…it was coushioning we thought. We know now that the helmet allowed a completely unnatural impact pattern that never occured in the days of Knute Rockne. 1000’s of head on collisions are causing degenerative changes in the brain and other structural tissues in a players head and neck. Helmets are now being regulated, as is the behavior (sounds like training gait).

I think the parody warning label is 100% true…”may cause leg injuries”. I never say a shoe by itself causes an injury…even it is completely dysfunction. The runner injures themselves. what are the attributable risks of various things (volume, intensity, form, shoes…). Kind of like heart attacks….what contributes the most out of all the risk factors. Turns out the attributable risk of lack of physical activity and smoking are the biggest players. cholesterol? pretty far down.

The inquisitive researchers may have the answer for Phil’s questions in the not too distant future.

Mark

Dr. Maffetone;

You mention that “one of the earliest published studies describing the harm from shoes came in the early 1950s.” I just wanted to point out a published study in our re-evolution library on the TRTreads web-site that is one of the oldest I am aware of describing the harm from shoes. It’s from almost 100 years ago…”The Soldiers Foot and the Military Shoe”, 1912, by Edward Lyman Munson. As you can tell from most military boots, dress shoes, and athletic shoes issued to our military today, we still choose to almost totally ignore the valuable information contained in this handbook. The traditional military boot has taken its toll, and I say the same for the traditional running shoe.

Sometimes the most difficult things to prove or explain are the obvious…….kind of like gravity and wind chill.

James Munnis